Introduction:

The production of electricity and heat is responsible for a significant fraction of the greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) that are produced every year globally. For instance, approximately 41.7% of annual GHG emissions come from energy used in residential, commercial and industrial buildings, according to Our World in Data. When you are aware of this, the importance of finding sustainable and clean sources of energy comes into view. When we have discussions about these types of sources, it is mainly focussed on wind and solar, so much so that even the mere utterance of the words “renewable energy” may conjure up thoughts of the countryside bathed in glorious sunlight with large rotating turbines with a splattering of solar panels in a picturesque internal view in one’s own mind’s eye. This is not unusual, typically when one is first introduced to the concept of renewable energy when they are children, it is overwhelmingly positive, at the very least it was when I was first introduced to the idea of renewable energy, so I’d forgive the romantic imagery. So, you may be able to imagine my surprise when I encountered a Ted-Talk lecture when I was in my mid-teens that was critical of renewable energy and thus I was thrust down a rabbit-hole and I discovered a part of the internet that was highly critical of renewable energy. It was from this discovery that eventually led to me writing the words of this article you’re currently reading.

If you’re reading this article, then it’s likely that you believe, and rightly so, that climate change is an observed phenomenon that is currently happening and it’s occurring due to humanity’s large-scale combustion of fossil fuels and land-use changes, and the subsequent release of GHGs into the atmosphere. Combine this with the factoid I brought to your attention at the beginning of this article, it’s easy to see the immense need to radically scale back our fossil fuel usage with suitable, and cleaner, alternatives. However, I wanted to use this article to explore something that may be interesting. Are renewables the best way forward? What role will they play in our future energy mix? What are their relative strengths and weaknesses? Are there any interesting developments that we should keep an eye on?

In this article, I’ll be using the term “renewable energy” quite a lot and by this I principally mean wind and solar energy although some of the statements I can use may apply to other types of energy generation- if there is anything interesting to explore with other electricity generation methods I reserve the right to explore them but I will mainly be focussing on solar and wind.

Defining terms:

Solar and wind are not monoliths and there are different forms of this type of energy production. For instance, solar can be separated into several different types depending on how exactly the energy is generated.

Photovoltaic (PV):

PV solar is generated using the photovoltaic effect to generate electricity. This effect is seen when a photon hits an electron and passes off enough energy to allow that electron to become free, creating a current.

Concentrated Solar Power (CSP):

CSP solar works in a more similar fashion to traditional fossil fuels than PV as it uses mirrors to reflect solar energy towards a receiver where it heats up a high temperature fluid to produce steam which is then channelled to turn a turbine to generate electricity.

Intermittency and the Duck Curve:

You will almost certainly be familiar with the idea of intermittency when it comes to renewable energy, it’s an unchangeable fact that the sun isn’t always shining, and the wind isn’t always blowing. Due to this, there are two main issues that stem from this, too much, or too little, power and at the wrong time. This can best be illustrated with a graph called the “duck curve”. Originally called as such due to its resemblance to its namesake, it was initially used to show the difficulty of integrating solar power into the Californian power grid. The difficulty stems from the inherent intermittency that comes from energy sources like solar and wind, levels of sunlight can vary over different timescales, as can the wind. As the sun sets or rises and the wind calms or blows, this can lead to large gluts or surges in power generation. This means that these sources must be supported through other strategies to keep the grid stable.

There are a surprising number of mitigations that can be used to level out energy production including:

Battery storage:

Battery storage is self-explanatory and has received a lot of media attention as it is becoming a larger part of the modern energy grid. Due to the mis-match between peak demand of consumers and peak generation from renewables, battery storage would take excess energy generated during peak hours and store it until there is a glut in production where this excess energy can be utilised to allow a steady flow of clean energy, keeping prices low and consistent.

Much like the solar energy they store, battery systems can come in lot of varieties:

Compressed air energy storage:

Surplus energy is used to compress air, once the energy is required, the compressed is used to spin a turbine to generate electricity.

Mechanical gravity energy storage:

This method stores excess renewable energy in the form of gravitational potential energy. An example of which could be pumping water up a hill into a reservoir and then releasing that water to pass through a turbine.

Flow batteries:

These are rechargeable fuel cells and most likely what you think of when battery storage is mentioned. They store excess energy in the form of chemical energy.

Time-of-use pricing:

Time-of-use pricing is the real-time change in the price of electricity to match its supply and demand. As you can imagine, when solar power is abundant and demand is relatively low, the price of electricity can plummet. For instance, Californian midday prices can fall to $15 per megawatt compared to $60 per megawatt between 5pm and 8pm. Additionally, the peaks and valleys of the duck curve are growing further apart as renewable energy production continues to grow. (Create a graph?)

Green hydrogen:

Green hydrogen is produced using excess renewable electricity to power electrolysis of water to split the molecule into its constituent oxygen and hydrogen. The hydrogen can then be burned later to produce energy conventionally- the result of this reaction is water vapour.

Fossil fuels:

When there are gluts in energy supply that are being generated from renewable energy sources, natural gas is often used to shore up electricity supply as they can be quickly ramped up and down to match the variability that comes with solar and wind.

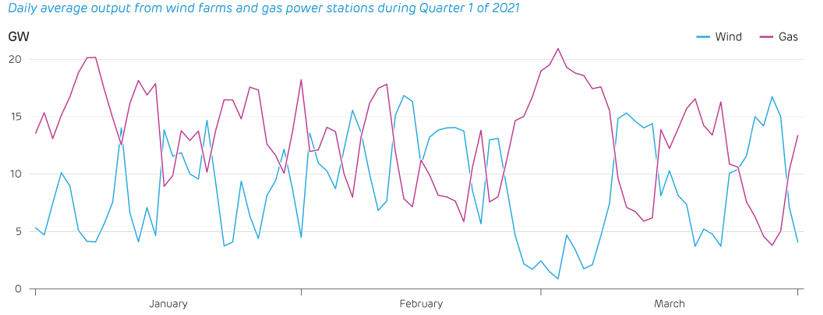

Figure 1- A graph showing how natural gas is used in the UK to shore up energy supply when there is a glut in wind generation.

As can be seen from the above table, there is a direct inverse correlation between the amount of gas being used for generation and that coming from wind, highlighting the reliance on gas this intermittency can create.

Land use:

It is also notable that wind and solar energy have relatively low energy densities, meaning the amount of energy available in the wind per unit area is relatively low. Wind and solar power have variable energy densities (owing to their intermittency described above) as they are weather dependent.

One argument that you may have come across a lot is that due to wind and solar being relatively dilute sources of energy, they need to spread over a huge landmass to match the quantities of energy generated by the fossil fuels they are replacing. Indeed, one of the strategies proposed to limit the intermittency associated with these types of generation is to spread them over continent sized land areas (Europe, for example) and integrate the various energy grids between the member states and share the electricity. It may not be windy in Germany or sunny in Spain, but it may be windy in the North Sea and sunny in Italy and if these energy sources can be built to a sufficient capacity and the grid is sufficiently integrated, it could be possible to slim down the disparity between peak demand and peak supply. This is especially true over large landmasses like Europe as it may be windy in Poland through the night when their energy demand is low so this power could be exported to Western Europe as their energy demand may still be high in the evenings (as they will likely be experiencing lower solar energy generation at this time of day anyway).

This is true on the surface if you look at the raw numbers. When compared to the land area required by a nuclear power plant, to generate a comparable amount of energy by wind and solar, you’d need a land area approximately 350x and 75x the size, respectively, according to the Nuclear Energy Institute. This is in part due to the capacity factor, or the amount of energy produced relative to the optimal amount, for these forms of energy. A standard nuclear power facility may have a capacity factor close to 90%. This is compared to between 32%-47% for wind and 17%-28% for solar.

The disparity isn’t quite as extreme when compared to natural gas, with approximately 100x more space being required by wind to match the energy output.

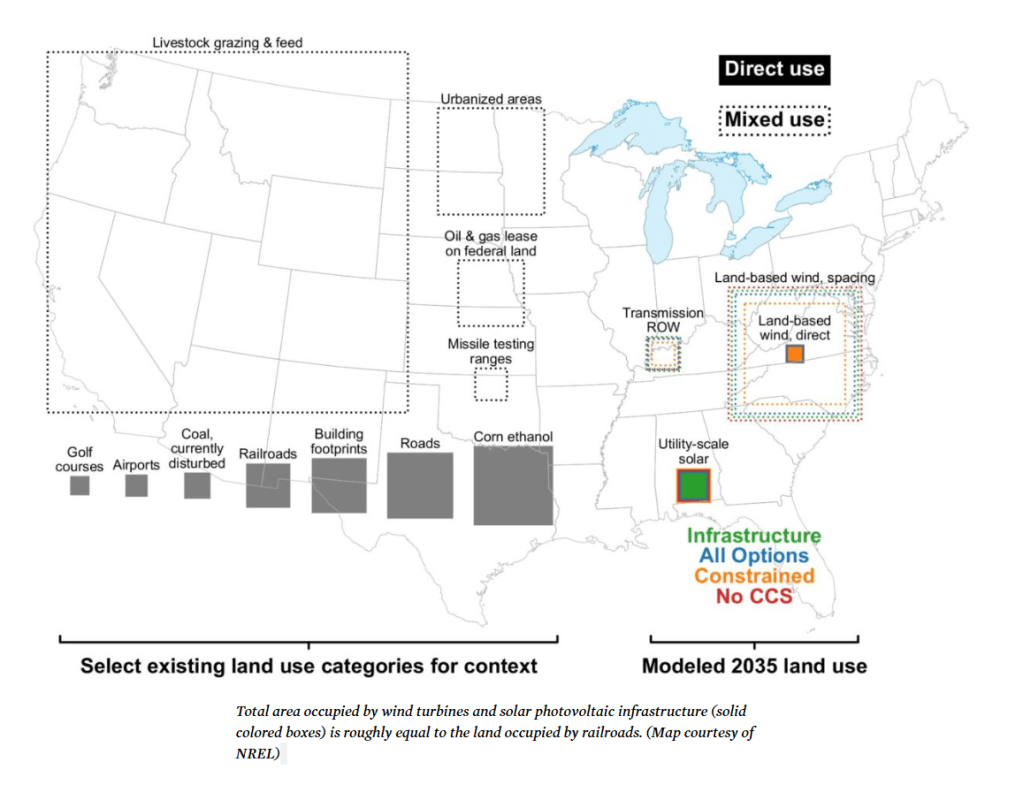

However, this can seem quite misleading as this assumes that this land is only used for energy generation. In fact, most of the land utilised for wind generation can have a dual-purpose including agriculture and grazing. Offshore can use larger turbines requiring less total area. Additionally, solar energy can be placed on less desirable land such as brownfield sites and abandoned mining sites, lowering the opportunity (what alternative use is there for this land). Also, rooftop solar has the additional benefit of being placed on land that is already being utilised. A report released in 2022 calculated the total amount of land required to power 80% of the USA’s electricity demand from zero carbon sources by 2023 and 100% by 2035 and found it would require approximately 19,700 square miles of wind farms, solar and long-distance transmission lines.

Figure 2- A map showing the total space required for different energy forms.

Water use:

The amount of water required for solar changes depending on the type of solar that is being used. You can easily see why CSP water needs would be much higher than PV water requirements. The cooling aspect of the CSP energy cycle accounts for much of the water requirement- meaning that a CSP plant can use upwards of 3,500 litres of water per MWh, compared to around 1,000 litres for a modern gas power plant, according to the European Union. Although this can be reduced dramatically if the solar plant uses dry-cooling technology (up to a 90% reduction) as it can reduce evaporative losses.

Solar PV has a much lower water requirement than CSP, and therefore much lower than traditional fossil fuels. They only require water as a part of their manufacture, cleaning and maintenance with some research saying they need between 0.08m3 to 0.15m3 per MWh, according to Bukhary et al, 2018. This is minimal water usage especially when compared to other thermo-electric plants like natural gas and nuclear, although this can change depending on if the power plant has a once-through cooling system or whether they have a recirculating system.

| Power generation method | Water requirement (per MWh) |

| Solar (PV) | 0.08m3 to 0.15m3 |

| Solar (CSP) | Up to 3,500, (wet cooling) |

| Natural gas (Once-through) | 7,500 – 20,000 gallons |

| Natural gas (recirculating) | 150 – 283 gallons |

| Nuclear (Once-through) | 25,000 – 60,000 gallons |

| Nuclear (recirculating) | 800 – 2,600 gallons |

| Wind power | 43 litres |

Figure 3- A table showing the water requirement of different water generation methods per MWh.

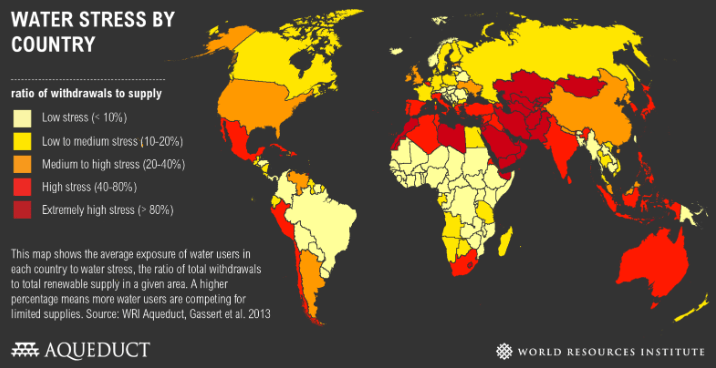

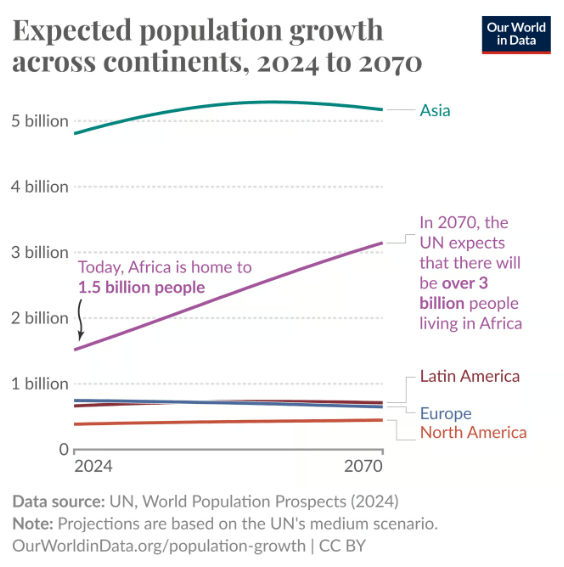

This is especially relevant when you consider the growing threat of water scarcity in the 21st Century. Much of the population and economic growth we are going to see over the course of the next 75 years will be in Africa, a continent that is often ravaged by drought. Meaning forms of generation that will not strain their already stressed water resources will be vital and renewables can provide that answer.

The electricity sector is the largest industrial user of water and is a big contributor to water stress. This is because thermo-electric power plants like the ones detailed above use large quantities of water in the production of electricity. As the demand for electricity increases, and as the demand for fossil fuel electricity increases, the pressure on water supplies will increase. This is even more dire when you factor in that the largest growth in electricity demand will be concentrated in the African region, which also coincides with where the largest population growth will occur over the next century and as can be seen from the figure below, some of these regions are already suffering from widespread water scarcity and stress that will only continue to worsen.

Figure 4- A map showing the water stress experienced by country.

Figure 5- A graph showing the projected population increase through 2070.

So, Africa will be facing a multi-pronged issue of rising electricity demand, increasing economic growth (which will drive electricity and water demand further) and an exploding population. If much of this electricity demand is satisfied through fossil fuel consumption then water scarcity will only increase, particularly due to worsening climate change which can drive water scarcity independently. This means that renewable energies should be a vital component of Africa’s energy mix to not only reduce carbon emissions, but to also lessen growing water scarcity in the region.

Mining impact:

The green energy transition will require a huge increase in the need for certain materials that are essential for the construction of green energy infrastructure. There are 26 minerals deemed necessary for green energy technologies (wind, solar, batteries and electric vehicles) and to reach the global goal of net zero by 2050, there will need to be a six-fold increase in the production of these minerals based on 2022 levels, according to the United Nations’ Environment Programme.

There are multiple issues that are associated with this level of mining. This article has mainly focussed on the direct environmental impact that renewable technologies have compared to other energy sources but as the title says, this article isn’t fully constrained too just the environmental. Some of the issues surrounding the green energy transition include geopolitics and global trade along with the social impact that these mining operations can have on the communities involved.

Environmental:

The environmental impacts associated with the mining and then processing of these critical minerals is plain to see with biodiversity loss and the destruction of habitats. Particularly since some green technologies have a higher mineral throughput than their conventional counterparts- a wind farm requires approximately nine times the minerals than a gas-fired plant and an electric vehicle requires six times the mineral throughput than a conventional internal combustion engine (ICE) car, meaning large increases in the demand for these minerals as organisations and governments invest heavily in carbon-neutral technologies, according to the IEA.

The mining for these minerals and elements come into two different flavours.

Chemical erosion:

This method involves removing the topsoil and creating a leaching pond where chemicals are added to the extracted earth to separate the metals. This method is common as it allows the rare earth elements to be concentrated and refined but these leaching pools can leak into the groundwater if they are not properly secured.

The consequence of this mining is drastic, for every tonne of rare earth elements (REE) that are processed the following impacts are created, summarised by an internal EURARE guidance report:

- 13kg of dust

- 9,600-12,000 cubic meters of waste gas

- 75 cubic meters of wastewater

- One tonne of radioactive residue

Overall, for every tonne of REE created- 2,000 tonnes of toxic waste are produced.

These environmental risks can have real-world consequences to the people exposed to the effects when they leach into the environment. For example, one AP report in 2019 found that more than 50 million gallons of contaminated wastewater from US mines flow into local water sources every day.

There is also a concern that as these minerals are increasingly drawn upon, as they have been for decades to create the high technology societies we inhabit, the “easy to mine” resources are dwindling and the remaining sources of these minerals are lower in quality, meaning less metal within the ore body, meaning more mining must be done for the same amount of metal.

It is imperative that we reduce our reliance on fossil fuels and that means drastically increasing the production of renewable energy from sources like wind and solar. However, it is also imperative that we don’t destroy the environment to save the climate. It is important that we take a critical look at the impacts that the mining and processing of the materials required by low carbon energy sources and ways to reduce these as far as possible, like improving community consultation processes, comprehensive mine closure procedures, remediation of abandoned mining sites, exploring ways to reduce or reuse mining waste. There has already been progress on these fronts whether that be through mining companies looking to ease tensions with local communities, or by investing in desalination so that seawater can be used instead of drawing on local freshwater.

Geopolitical:

Geopolitics have become increasingly mainstream in the last few years, first brought mainstream attention with the supply chain shocks and shortages of vital equipment during the COVID-19 pandemic and then further exacerbated by Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine, the conflict between Israel and Palestine and now most recently it has been brought to the foyer with the rising tensions between the United States and China through their, at the time of writing, escalating trade war. Some experts claim that we are seeing the rise of a multi-polar world, a sudden departure from the unipolar world that we have inhabited since the end of the Cold War in 1991 with the collapse of the Berlin wall and the Soviet Union.

From this perspective, we have entered a different world where the tensions between great power states is the dominant feature of our geopolitical environment. With rising tensions between the incumbent Western-led order and the neoteric status of China as pre-eminent power on the global stage. There is a discussion that is long overdue regarding the supply chains that feed the construction of the renewable energy infrastructure of the 21st Century.

As previously mentioned in this article, the green energy transition is reliant on a select number of minerals and rare earth elements and much of the global supply of these has been monopolised by China. In 2016, about 85% of the REE market was produced by China producing 120,000 tonnes of REEs in 2018. For comparison Australia came in a distant second, accounting for only 10%. The issue with this monopolised control of this vital commodity is that it hands China a vast amount of geopolitical leverage. As countries transition to cleaner energy sources, they become increasingly reliant upon China for their energy infrastructure. And China has shown that they’re not shy about flexing this market dominance if it suits them as was shown in their export controls of these minerals to Japan in 2010 as a punishment for the Japanese detention of a Chinese captain. For a more recent example, in response to the escalating trade with the USA, China restricted the export of seven REEs that were critical to the American defence industry. These show that the Chinese are not afraid of using their dominance in the REE market for their own benefit.

Knowing this, we should be wary of how much reliance we grow on the Chinese state. Even further, there has been a recent spat between the United Kingdom and the Chinese company Jingye, which own the British Steel complex in Scunthorpe which has resulted in the quasi-nationalisation of the works by the British government due to the perceived importance of steel production for the manufacture of vital defence equipment (this steel works housed the last remaining blast furnaces capable of producing virgin steel). The power and influence China has over these REE (and green technologies more generally) is frightening especially when it is juxtaposed with their willingness to shut off the source of these minerals when they are challenged. All of this is to say that there needs to be a greater sense of urgency toward weaning ourselves off cheap Chinese products, especially ones of critical importance to national security.

Social:

The social and environmental impacts of the mining necessary to build the necessary green energy infrastructure to power civilisation cleanly go hand-in-hand. One of the ways China was able to dominate the REE market was through low-cost, high pollution methods to secure these resources which allowed them to compete internationally against their more scrupulous and better regulated rivals. The end result of all this is not just the extreme environmental degradation but the social impacts that come along with it.

There are several examples of poorly managed REE mines in China. For example, Bayan-Obo is the largest REE mine in the world and what comes with it is the world’s largest tailing pond. The world’s largest tailing pond that is without a sufficient lining, resulting in the seeping of its contents into the groundwater and eventually the Yellow River which is a vital source of drinking water.

The result of encountering the toxic pollutants associated with REE mining can be quite devastating. For instance, the Chinese government itself has acknowledged the existence of “cancer villages” where a relatively large number of people have been afflicted with cancer due to their long-term exposure to this type of pollution. With this pollution, comes civil disobedience as there have been small-scale protests against the rampant disregard these mining operations have for the local communities in these areas. In Yulin, ten protesters were arrested for protesting in May 2018, similar demonstrations happened in Zhongshan in 2015.

In response to these outcries, Chinese mining companies have begun investing in mining operations in Africa where it is unlikely they will treat the inhabitants, some of the world’s poorest, any better. China secures commercial mining rights to these nations in exchange for infrastructure investment. Although some are worried that this is a strategy being employed by the Chinese state to lock these countries into an inescapable debt trap.

I don’t mean to be coming down as overly pessimistic on renewables but in order for the green transition to truly be green and for it to lead to a secure and peaceful future requires that these issues outlined above be tackled in a very serious and very urgent manner.

End-of-life recycling:

All good things must come to an end eventually and renewables are no exception. The average lifetime for a solar panel is approximately 30 years, this is when the solar panel is at its peak generating capacity, after which there will be a slowly diminishing return of energy produced. As for wind turbines, this lifetime is approximately 25 years, depending on location and maintenance. This begs the question, what happens after this lifespan has ended? Can these renewable energies be responsibly recycled with minimal impact to the environment? If so, is this a likely outcome?

Wind:

According to the National grid, about 96% of a wind turbine is made from recyclable materials as the outer shells, shafts, gearing and electrical components are made from steel, copper and aluminium. The blades themselves are made mostly of fibreglass. This is the main issue surrounding the disposal of wind turbines as fibreglass which is difficult to recycle, it is usually incinerated or disposed of in landfills. With much of the wind capacity being installed in the last decade or two, it is estimated that there will be approximately 10,000 – 20,000 blades that are expected to be at the end of their life span between 2025 and 2040 in the United States. Models produced by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) suggest that the recycling rates for these turbine blades could be as high as 78%.

However, not all wind turbine blades are destined for the scrap heap. There are some innovative ways these materials are being repurposed. For instance, the fibreglass content can be used in the production of cement and there is increasing research in finding alternative materials to make wind turbines out of, like thermoplastic resin which is biodegradable.

Solar:

It is estimated that there will be approximately 60 billion tonnes of PV waste produced by 2050. Fortunately, silicon solar modules, which make up approximately 95% of the market, are made mostly of glass, plastic and aluminium which are widely recyclable- around 80% of a solar panel’s components can be recycled.

A surprisingly optimistic conclusion:

“There are no solutions, there are only trade-offs.” This quote, spoken by Thomas Sowell, summarises that every “solution” that we are capable of conjuring has a fundamental cost and benefits associated with it- renewables are no different. The end result of progress is not the solving of problems but simply replacing today’s problems with less bad problems tomorrow. This is to say that renewable energies like solar and wind are not perfect, but they don’t need to be. They simply need to be better than the energies they are set to replace.

Yes, renewable energies have some flaws associated with their implementations, some of which are fundamental and inherent to their design but so do fossil fuels. The path that needs to be taken going forward is on producing and implementing these renewable energies in a way that is environmentally friendly, including ensuring that we have the adequate infrastructure in place to recycle these components as much as it feasible when their lifecycle ends, ensuring the supply chain for these components are as separate from Chinese influence as possible and to ensure that these technologies can displace fossil fuels as quickly as possible for the sake of the Humanity’s future.