Abstract

This dissertation sets out to answer multiple different questions.

- Do species that have similar 16S rRNA genes inhabit similar environments in terms of the temperature and salinities they will have to tolerate?

- Do extremophiles (whether tolerant to extreme heat or salinity) have a broader range of environments that they can inhabit relative to non-extremophiles? i.e., will you see more extremophiles in non-extreme environments compared to non-extremophiles in extreme environments?

The analysis did this choosing a range of organisms (three methanogens and three SRBS, one thermohile, one halophile and one non-extremophile), using BLAST to search for genetically similar organisms using the V4 region of their 16S rRNA gene, inputting their FASTA data into MEGA to create phylogenetic trees that represents how similar the organisms are genetically and their source environment and allows for comparisons between the two.

The analysis concludes that the greater the similarity between two species 16S rRNA gene, the greater the likelihood that they share similar environments that have similar temperature and salinity conditions. This could have a profound impact in the future as this could be used as a way to quickly surmise what type of environment an organism may inhabit and it could provide some insight into what that organisms tolerance to temperature and salinity are, which save a huge amount of time and research funding.

Additionally, the analysis also shows that there is surprisingly small presence of extremophiles in non-extreme environments. Further research will be needed to understand why extreme organism seem unable to compete with non-extreme organism in non-extreme conditions.

Introduction

Importance of this research:

The geochemistry of the air, soil and water is incredibly important for a whole series of different environmental factors. This geochemistry is mediated by a whole host of different organisms, and different organisms can have differing impacts on these environmental factors; knowing this, it is incredibly important to know what environmental conditions are conducive to the growth of which micro-organism species so that it could be possible to change the conditions of an area to alter the growth of the micro-biome to help improve the material conditions for humans.

The Temperature and salinity of an environment are some of the biggest determinants of the size and makeup of a microbial population and that’s why this meta-analysis is focussing on these two factors in particular.

This research is important because of the wide range of applications that are possible from this type of research. These applications include, hydrogen storage, soil pollution management, water quality improvement, uranium disposal and climate change mitigation. The paragraphs below highlight some of the many applications that microbiology and subsurface microbial communities can have and why understanding why certain parameters (namely temperature and salinity although others are also important) can change the microbial makeup of certain environments and how this can have huge impacts, either positive or detrimental.

Hydrogen storage:

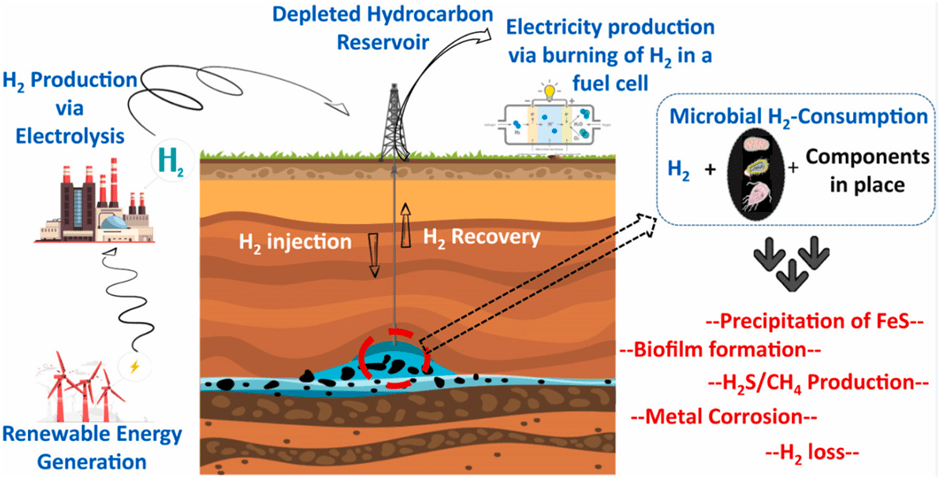

Renewable energy sources, like wind and solar, are going to be crucial to help mitigate and combat climate change. However, these energy sources have major challenges that will need to be overcome to help maximise their impact. One of these challenges includes the disparity between maximum supply of energy and the maximum demand for energy. When renewable energy is supplying the most energy is not necessarily when that energy is most in demand and therefore a storage solution is needed. Hydrogen could prove to be a valuable method of storing this excess energy by using the renewable energy generated to power hydrogen production via electrolysis of water. An example of this is provided below in figure 1. However, this will require appropriate storage areas. Such areas could include old hydrocarbon reservoirs where hydrogen is pumped in under pressure and stored. Yet, for this to be viable, the microbiology of the reservoir would have to be understood to prevent any microbiological communities that may inhabit the reservoir from utilising the hydrogen stored within. This is because hydrogen can act as an electron donor for sub-surface microbial processes which may end up consuming the stored hydrogen.

Therefore, it would be crucial to understand how temperature and salinity (among other factors such as pH and pressure) of the reservoir would hinder or encourage the growth of certain microbial species that may, or may not, deplete the stored hydrogen. Thaysen et al, 2021, screened 42 depleted oil and gas fields to study their microbial growth. They found that five of the screened fields were sterile in relation to hydrogen consuming micro-organisms due to extremely high temperatures (Above 122◦C), this effectively shows that temperature can limit the growth of certain micro-organism communities.

Additionally, there are three major hydrogen consuming micro-organisms that are the subject of much research. These include:

- Hydrogenotrophic sulphate reducers that couple hydrogen oxidation to sulphate reduction to produce hydrogen sulphide.

- Hydrogenotrophic methanogens that convert carbon dioxide to methane by oxidising hydrogen

- Homoacetogens that couple hydrogen oxidation to carbon dioxide reduction to produce acetate.

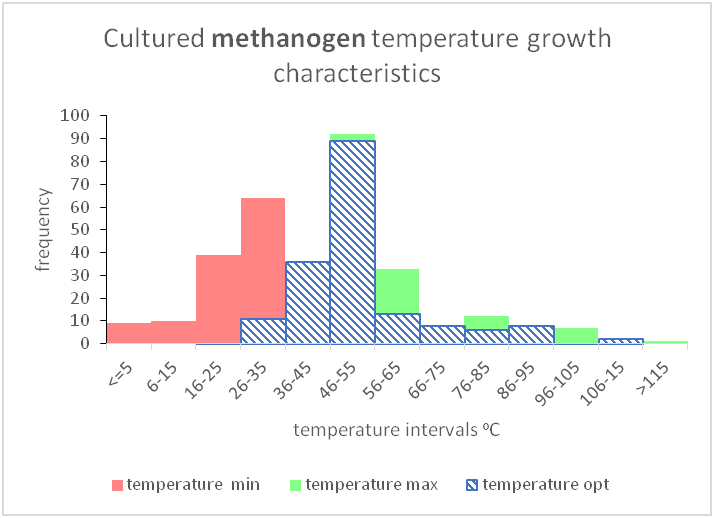

This presents further challenges and further opportunities for research as all of these can utilise hydrogen as an energy source, but all have differing optimal requirements for temperature and salinity, not only between different species types but also within those species. For instance, most cultivated hydrogenotrophic methanogens are mesophiles that thrive at temperatures of 20◦C -45◦C, however, many cultivated sulphate species reducing micro-organisms (SSRMs) have an optimal temperature of 20◦C -30◦C or 50◦C -70◦C, depending on the strain (optimal temperature can vary within species) and homoacetogens have optimal growth temperatures of 20◦C -30◦C, although 8 strains have been shown to have optimal growth temperatures of greater than 60◦C. These variances can make selecting an appropriate hydrogen storage area difficult (Thaysen et al, 2021).

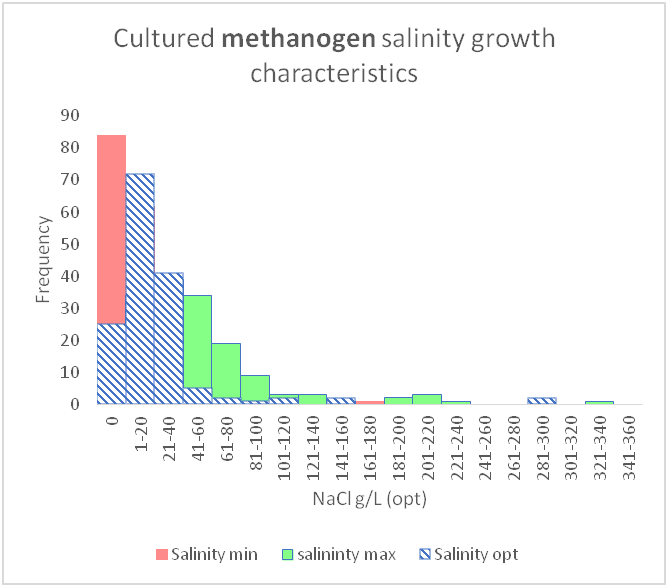

A similar problem is also present in the salinity tolerances of these three different micro-organism classes. Hydrogenotrophic methanogens have optimal salinities of up to 0.77M NaCl. SSRMs have optimal tolerances of 0-0.4M NaCl, similar to that of homoacetogens although the salinity tolerances of this group of micro-organisms are poorly understood. Again, there is considerable variation within groups of species, further complicating the selection process for appropriate hydrogen storage sites.

| Species group | Optimal growth temperatures | Optimal growth salinities | Comments |

| Hydrogenotrophic methanogens | 20◦C -45◦C | Up to 0.77M NaCl | Some methanogens can tolerate temperatures above 60◦C Maximum temperature appears to be 122◦C |

| Sulphate species reducing micro-organisms | 20◦C -30◦C 50◦C -70◦C | Up to 0.4M NaCl | Full range of growth is 10◦C-106◦C Critical temperature appears to 113◦C |

| Homoacetogens | 20◦C -30◦C | Up to NaCl (poorly understood) | Limiting temperature growth appears to be 70◦C -72◦C |

This research highlights the complexity of sub-surface microbial processes, the complications associated with selecting appropriate hydrogen storage sites and the need for much more research to be conducted (Thaysen et al, 2021).

Soil pollution management:

Industrial processes are an essential and ubiquitous part of daily life, both in industrialised and industrialising societies, and this industrialisation is only going to become more widespread as we progress through this century. However, this industrialisation has had many negative impacts on the environment. One of these consequences is that of soil pollution. The by-products of industrial processes can leach out into the environment and into the soil and this can lead to several different negative consequences.

This soil pollution can come in many forms including excessive levels of nitrogen and phosphorous from chemical fertilisers which reduce soil biodiversity by encouraging the growth of a few highly competitive species. A reduction in soil biodiversity is detrimental in multiple ways as it makes ecosystems less able to adapt to stress and can make them more vulnerable to the spreading of disease or from pests which also causes concerns for commercial agriculture and humanity’s ability to feed itself.

Whilst soil pollution may have impacts on biodiversity which can harm human health, reduction in access to medicinal plants for example, soil pollution also has direct impacts on human health as well. Wu et al, 2018, investigated soil pollution near an electronics manufacturing facility and assessed the soil for a number of different heavy metals, namely Cr, Cu, Zn, As, Cd, Ni and Pb. The total concentrations of these metals ranged from 3738 to 5173 mg/kg. Unsurprisingly, the concentrations were highest near the commercial area, however high levels of these heavy metals were also found in nearby farmland and residential areas. This poses a significant danger as it shows that humans are in direct contact with land polluted with significant levels of heavy metals. The potential impacts of excessive exposure to some of the aforementioned heavy metals are summarised in the table below.

| Heavy metal | Health impact of excessive exposure |

| Cr | Lung, nasal and sinus cancer if inhaled chronically (OSHA, 2013). |

| Cu | Possible link to developing Alzheimer’s disease (National Academy Press, 2000). |

| Zn | Impacted cardiovascular function (Office for Dietary Supplementation, 2021). |

| As | Dermal lesions and skin cancer (Rasheed, Slack and Kay, 2016). |

| Cd | Lung cancer and kidney dysfunction (OSHA, 2013). |

| Ni | Lung, throat and stomach cancer (Public Health England 2009). |

| Pb | Nervous, skeletal, endocrine and immune system damage (NHS- Scotland, 2021). |

This shows that heavy metals can have severe negative consequences, especially in children, so any method that can limit exposure will be beneficial (Wu et al, 2018).

A process known as “bioremediation” can be used to help aid in the regeneration of soils to improve their quality and limit the spread and concentration of heavy metals through the use of micro-organisms that have to been shown to be able to sequester these soil pollutants. For instance, Aspergillus Niger has been shown to be able to effectively remove As (V) and As (III) (Chibuike and Obiora, 2014). Additionally, Methanothermobacter Thermautotrophicus was shown to be able to reduce Cr (IV) to Cr (III) (Kapahi and Sachdeva, 2019). This shows that micro-organisms have some application when to it comes to clearing up heavy metal pollution from soils. In order to use this process correctly, knowledge about how certain species interact with certain levels of temperature and salinity will be important to gain optimal results, particularly deep in the sub-surface. This is particularly important as not only can higher temperatures improve or hinder the ability of micro-organisms to sequester dangerous soil pollutants, but higher temperatures may also increase the solubility, and hence the mobilisation, of heavy metals, which make them a much bigger problem. Therefore, more research into this interaction between temperature, micro-organism activity and heavy metal solubility will be important to elucidate.

Water quality improvement:

Much like soil, water is also susceptible to pollution from both man-made and naturally occurring pollution which will degrade its quality which can cause many negative health effects to humans. Similar to soil, water is also vulnerable to chemical fertiliser run-off which can lead to eutrophication. However, it is also possible to use micro-organisms to aid in ameliorating this water pollution. One such example is the use of a process known as bioaugmentation, which is the use of archaea or bacterial cultures to aid in the degradation of a groundwater pollutant, helping to reduce overall pollution and its impact. Again, much like in the previous two examples, understanding how the temperature and salinity of the groundwater being treated would impact the ability of the microbial cultures to degrade the contaminant would be crucial in understanding when the use of this technique would most optimal or when a different approach should be considered in lieu of it.

Uranium Disposal:

The disposal of uranium resources is necessary as uranium has a few key uses; including power generation, medical applications and in national defence. As a result, a way of managing this waste is necessary. In the UK and many countries around the world, a strategy known as “geologic disposal” is undertaken; this involves the construction of deep radioactive waste repositories between 200m and 1,000m allowing for the safe storage of hazardous radionuclides (Ewing, Whittleston and Yardley, 2016). It was long thought that microbiological activity was non-existent beneath the Earth’s surface, but it has since been discovered that biological activity can be present up to a few kilometres beneath the surface. Whilst this activity is much diminished relative to surface activity, it can still have implications in regard to uranium disposal.

Microbial communities can be hazardous to uranium disposal. For instance, radioactive waste is stored within metal containers, which are generally resistant to corrosion but over long time periods this metal can start to corrode. This corrosion can form hydrogen which can be used to fuel sulphate-reducing bacteria which are of particular concern as they can produce hydrogen sulphide which can further exacerbate the corrosion process and increasing the likelihood that a leak will occur, which could potentially pose a threat to humans and nearby ecosystems due to the leakage of hazardous material (Gregory and Barnett, 2018).

However, microbial communities can be beneficial to uranium disposal. For example, after the closure of the repository, micro-organisms can produce carbon dioxide and this can create an anoxic environment which will allow methanogens to combine hydrogen and carbon dioxide to form methane, lowering the pressure of the repository, reducing the risk of a malfunction. In addition to this, micro-organisms can also be used to help bioremediate soil pollution from uranium. This is because a wide range of micro-organisms are known to be able to convert soluble uranium (IV) to insoluble uranium (V) which greatly restricts the transport of the uranium within soils and groundwater and could be used to prevent uranium leakage within repositories or help remediate them when they do happen. In conjunction to this, uranium can also be a potent pollutant and can be mobile within soils and groundwaters when it forms soluble complexes with organic molecules that are produced as by-products when intermediate waste is degraded, and a wide range of micro-organisms have been found that are able to degrade these soluble complexes which can help reduce the environmental impact of uranium waste repositories (Gregory and Barnett, 2018).

Due to the sensitive nature of the elements involved and the potentially huge benefits and drawbacks that the microbiology of these repositories can have, it would be crucial to understand how the temperature and salinity of the surrounding ecosystem will help encourage or retard the growth of certain classes of micro-organisms that may have positive or negative impacts on the repository.

Climate change mitigation:

Climate change is one of the pressing issues of the 21st century. Considering this, every tool at our disposal should be considered as we contemplate the best ways to help mitigate its most deadly effects; one of these potential tools is the utilisation of micro-organisms.

Microbial processes play a central role in the regulation of the climate. For instance, they control the biogenic production of multiple greenhouse gases including carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide and it is also likely that these micro-organisms and their associated microbial processes respond quickly to climate change. While it is currently unclear whether these microbial processes have a positive or negative impact on the climate, considering the scope of the potential problem, it is important to investigate the impact that changes in temperature and salinity can have on microbial communities whilst the overall climate impact of the processes they carry out are elucidated (Singh, Bardgett, Smith and Reay, 2010).

It has been widely accepted that microbial processes have been a predominant driver of climate change and the atmospheric concentrations of several important gases for throughout much of Earth’s history.

Carbon dioxide released through the anthropogenic burning of fossil fuels is dwarfed by the amount of carbon dioxide released through the photosynthesis and respiration of organisms; meaning that current concentrations of atmospheric carbon dioxide is mostly controlled by the net balance of photosynthesis and respiration taking place biologically on the planet. In the oceans, photosynthesis is carried out by phytoplankton and respiration is carried out by autotrophic and heterotrophic organisms. Whilst on the land this is dominated by higher plants, micro-organisms are still important drivers of carbon exchange in soils through the processes of decomposition, heterotrophic respiration and through the modification of the nutrient availability within the soil. Approximately 120 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide are sequestered by primary production on land, with 119 billion tonnes being released, half of which is released by respiration by heterotrophic soil micro-organisms. Considering the vast amounts of carbon dioxide that are released and sequestered through micro-organisms, understanding which organism are responsible for the majority of this sequestration or releases and understanding how these micro-organisms respond to changes in temperature and salinity, especially in the oceans, could provide a vital method for combatting changes in climate by altering how much carbon dioxide is released or sequestered by micro-organisms (Singh, Bardgett, Smith and Reay, 2010).

This research is even more important as these same principles could be applied to micro-organisms, and their microbial processes, which control and influence the concentrations of different greenhouse gases (methane and nitrous oxide, for instance), some of which have very potent warming capabilities. Methane, for example, has a warming capability 25x more potent than carbon dioxide (EPA, 2021) and nitrous oxide has a warming capability of 265-298x that of carbon dioxide meaning the control of these gases through the use of micro-organism manipulation could reap potentially huge benefits for mitigating climate change (Grace and Barton, 2014).

Astro-biological Implications:

The study for extra-terrestrial life is one of the greatest scientific pursuits undertaken by humanity and much of the search for life beyond our own is that life that is microbial in nature. One of the key questions that this analysis set out to answer was what types of environments can micro-organisms inhabit, whether they be extremeophiles or not. Water is the main factor that limits or permits the production of life; micro-organisms have been found in virtually any habitat where water can be used, showing the capacity for life to survive and evolve under the most extreme of conditions (Merino et al., 2019). Therefore, it is essential to know not only the minimum and maximum values of these conditions (pH, temperature, pressure, acidity, salinity, etc.) that are tolerable and how these factors can interact with each other…

This report focuses mainly on methanogens and SRBs and only considers temperature and salinity tolerances but even these variables can change considerably across the Earth and can greatly influence community structure. For instance, the most extreme halophile currently known is Halarsenatibacter silvermanii, which has been found to inhabit Searles Lake in California, USA, which has a optimal salinity of 35% NaCl. Additionally, temperature fluctuates immensely across the surface of the Earth as it ranges from 98.6 (Scambos et al, 2018) in East Antarctica up to almost 500 (McDermott et al, 2018) in some deep hydrothermal vents. Current microbial life, as it is currently understood, can survive from temperatures ranging from -25 (reported temperature minimum for Deinococcus geothermalis)(FrÖsler et al,2017) to 130 (reported temperature maximum for Geogemma barossii) (Kashefi and Lovley, 2003). As can be seen from these few examples is the huge variation in environmental conditions that micro-organsims can survive. Further research into this study could look for additions to the prior examples given but could focus on how different factors interact with each. Hypothetically, how could a thermophiles ability to resist a certain temperature (say 80) change as other variables (like salinity) are altered.

Methodology

How is it done?

With the growing abundance of scientific research being produced concerning micro-organisms and their environmental niches, in no small part due to their huge range of potential applications mentioned above, meta-analysis continues to be a critical way of keeping scientists abreast of the latest scientific research. This is particularly important when different studies vary based upon their experimental design and overall quality.

A meta-analysis is begun by selecting a specific question to be answered, this allows for relevant research to be identified and assessed for relevance and quality. A preliminary search will also be needed to ensure that such a question has not already been answered. Due to the need to judge studies based upon quality and relevance, there is a necessary need to formulate criteria to judge any perspective studies against. For instance, since this meta-analysis is mainly concerned with the impact of varying degrees of temperature and salinity on micro-organism species, factors such as pH and soil/water nutrient levels will be left out and due to the vast scope of the literature that has been published it may also be necessary to restrict the scope to a select few organism classes- sulphate reducing bacteria and methanogens.

Since a meta-analysis concerns the summation of all the scientific literature concerning a particular topic, a search strategy becomes necessary. Microbiology hosts a number of prestigious journals that hold hundreds of studies that will be relevant when investigating this question. These journals and other applications available for searching include.

- Google Scholar

- PubMed

- Web of Science

- BIOSIS Citation Index

- ASM (American Society for Microbiology)

- SILVA- holds ribosomal RNA sequence data.

- NCBI (National Centre for Biotechnology Information)

The studies published within these journals can be imported (on to EndNote, for example). It may be possible that a study was published into two different journals at the same time so any duplicates would have to be removed using the study’s title, year of publishing and the author of the study. From here, the results could be exported onto one Endnote file. Once all of the research has been compiled into one file, they can be screened based upon the criteria previously mentioned. In this case, based upon the environmental factors and the micro-organism species that are being investigated.

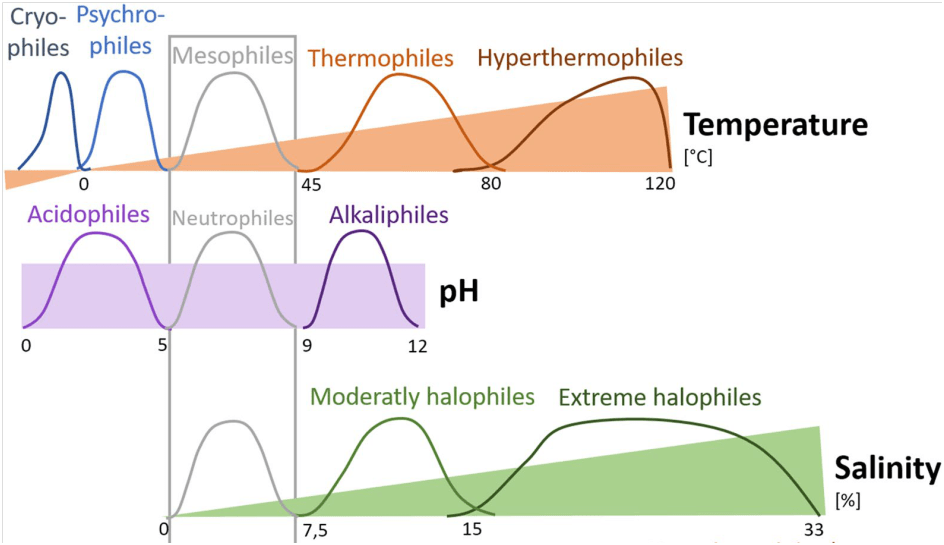

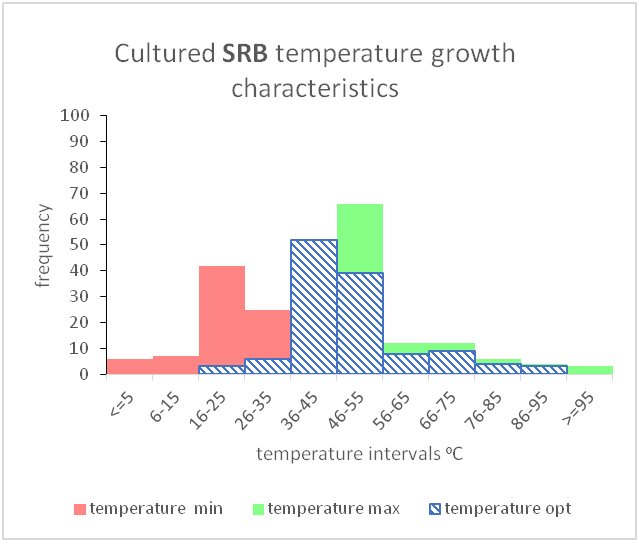

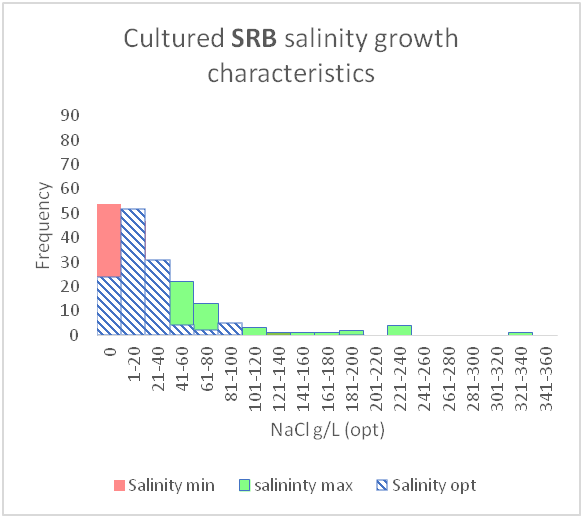

After the studies have been compiled and vetted for relevancy and quality, a statistical representation can be carried out. For instance, an example of the types of statistical representation that can be carried out for this meta-analysis could include 2D plots like figures 7-10 or could include a 3D plot showing the maximum, minimum and optimal temperatures and salinities of methanogen and SRB species, this could help identify gaps that are shown in conceptual models, like those shown in Figure 2 below. However, a potential problem with this method is that microbiologists prefer to isolate a species in situ and then test the conditional limits of that species as opposed to isolating it under a broad range of conditions.

Described above is a generic start when meta-analyses are undertaken, below is a more tailored methodology. Since this dissertation is setting out to answer how 16s rRNA genes influence environmental distribution and the range of environments different organisms inhabit, the first step taken was to identify 6 main organism we could investigate. These organisms were split equally between methanogens and Sulphate Reducing Bacteria (SRBs). In each group one thermophile, one halophile and one non-extremophile organism was chosen. This was so we could investigate similar organism and determine whether their gene similarities influence their environmental distribution and whether extremophiles and non-extremophiles have some overlap in their environmental distribution.

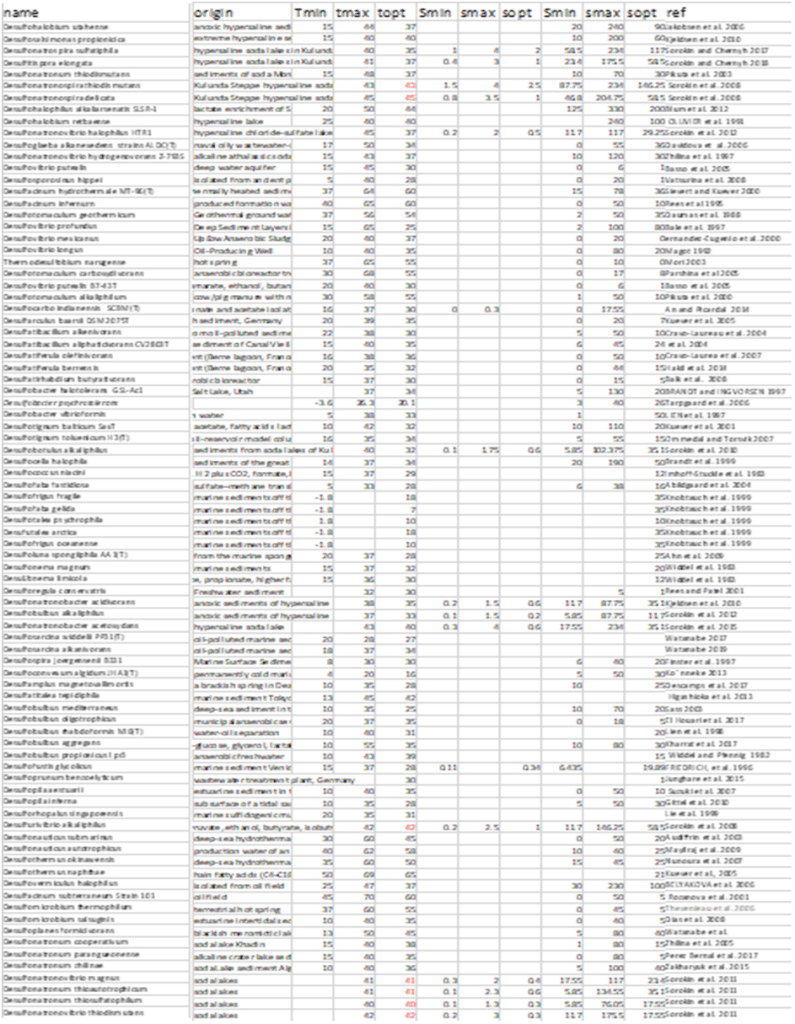

Six organisms were chosen to be analysed. They were chosen from a list of Methanogens and SRBs that were taken from the scientific literature and were then compiled onto an Excel spreadsheet which shows their temperature and salinity tolerances. This spreadsheet allowed bacterial organisms to be chosen based upon their temperature and salinity tolerances. The table shows the organisms that were selected and their respective tolerances.

| Organism | Min temp (◦C) | Max temp (◦C) | Opt Temp (◦C) | Min Salinity | Max salinity | Opt salinity |

| Solidesulfovibrio fructosivorans | 20 | 45 | 35 | 0 | 40 | 0 |

| Desulfovibrio salinus | 15 | 45 | 40 | 10 | 120 | 30 |

| Desulfotomaculum thermocisternum | 41 | 75 | 62 | 0 | 47 | 12 |

| Methanocorpsulum Labreanum | 25 | 40 | 37 | 0 | 29 | 0 |

| Methantherobacter Thermophilus | 37 | 74 | 55 | 0 | 10 | 10 |

| Methanotorris Igneus | 45 | 91 | 88 | 8.9 | 53 | 17 |

Once, these 6 organisms were chosen. Their 16s rRNA genes were found and a region called the V4 region was determined. The 16s rRNA gene was used as all bacterial species have a 16S rRNA gene and so it can be used for identifying and classifying bacterial species (Clarridge, 2004). Additionally, the V4 region was chosen as this area has the maximum nucleotide heterogeneity and would therefore allow us to have maximum discriminatory power when finding similar organisms through the NCBI BLAST function (Soriano-Lerma et al., 2020).

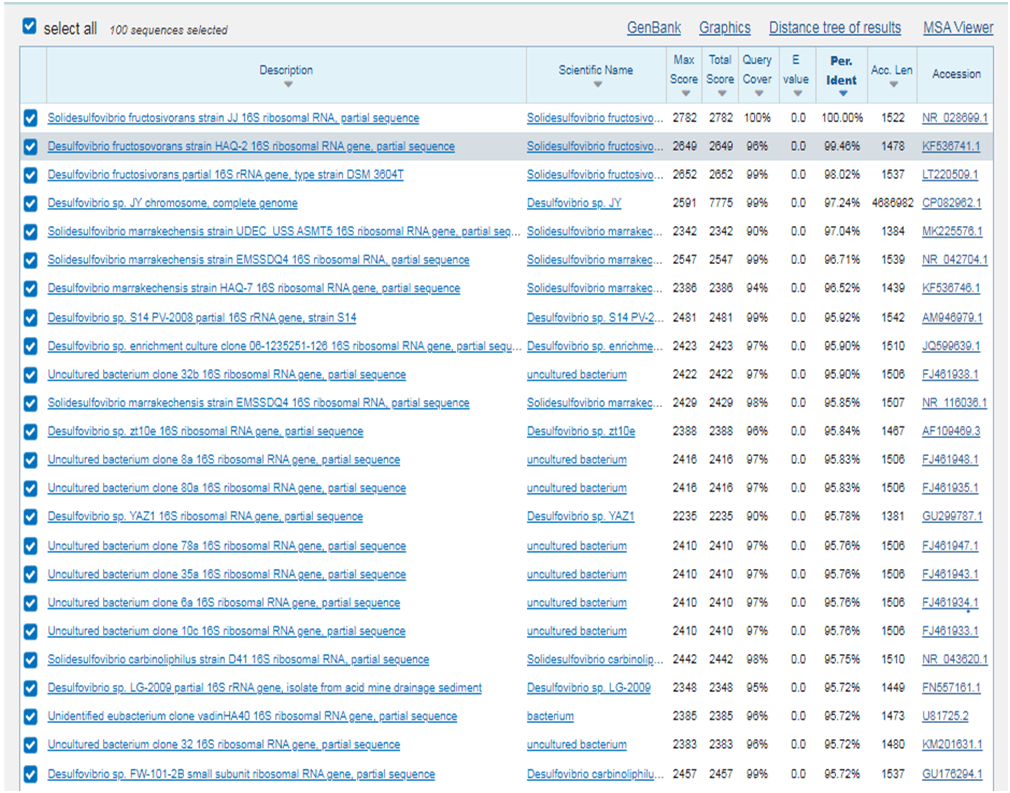

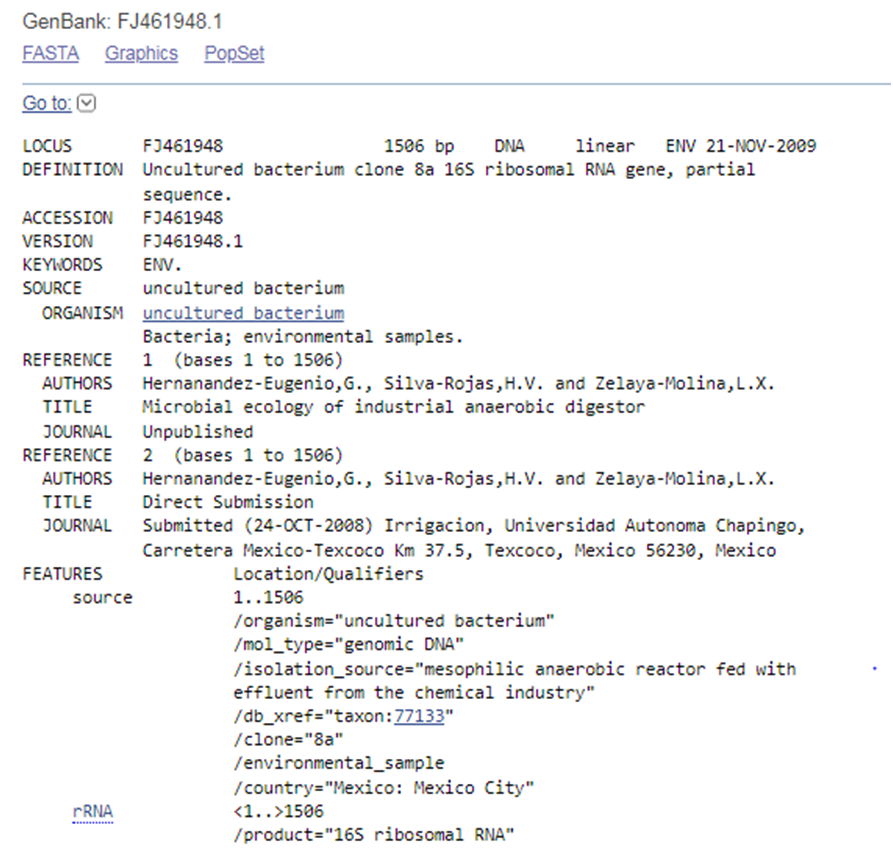

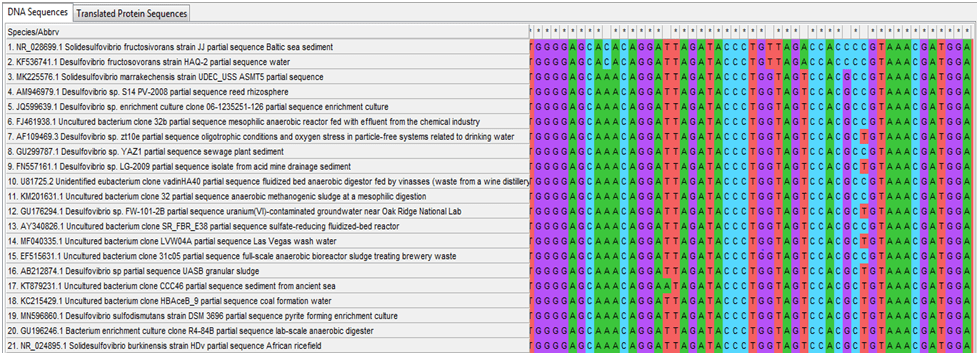

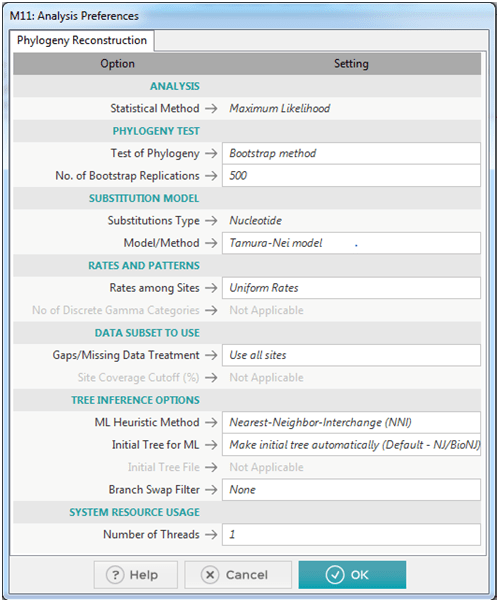

Once this V4 region was identified it was put into the NCBI BLAST function and a list of similar bacterial species were found, approximately 15-20 related species were chosen. The GenBank and FASTA data were tabulated in separate documents (this data included any relevant research, the environment where the bacteria were isolated from). The similarities differed quite dramatically between different related species as some species would have all their related species that were found to be above 97% similarities whilst others had similarities that could drop as low as 90%. Once all of the FASTA data had been tabulated, this allowed for the genetic sequences to be inputted into MEGA (Molecular Evolutionary Genetic Analysis which can be used to create phylogenetic trees which shows how different species are related to each other based upon their genetic code). The sequences were inputted, aligned using the software and then any redundant were snipped away. After this, an analysis (maximum likelihood analysis) using the software was conducted and phylogenetic trees were created showing graphically how different species are related and alongside this the environmental source data gathered from the GenBank was input to allow a comparison to see what types of habitats are inhabited by different organisms with different temperature and salinity tolerances.

Results

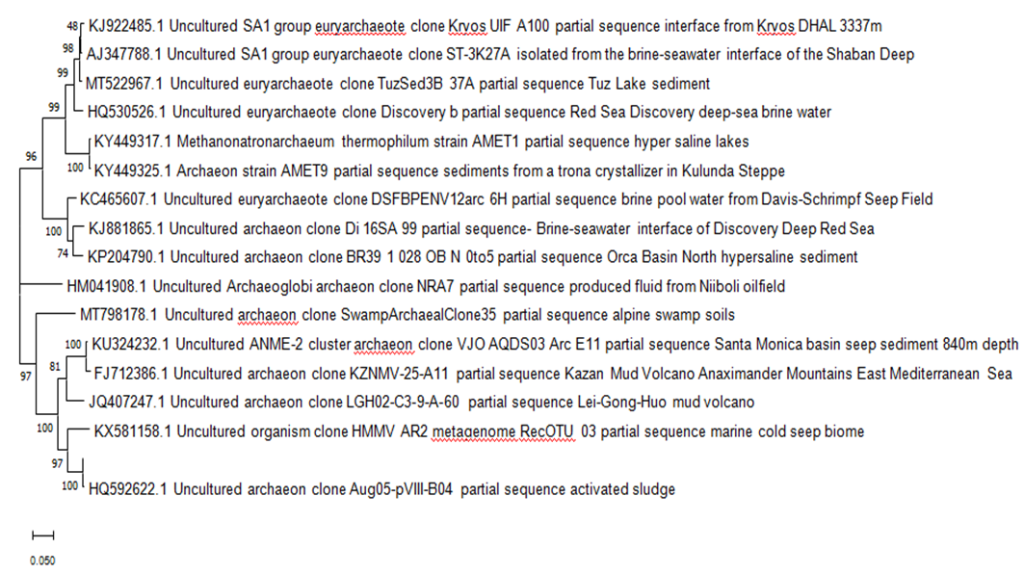

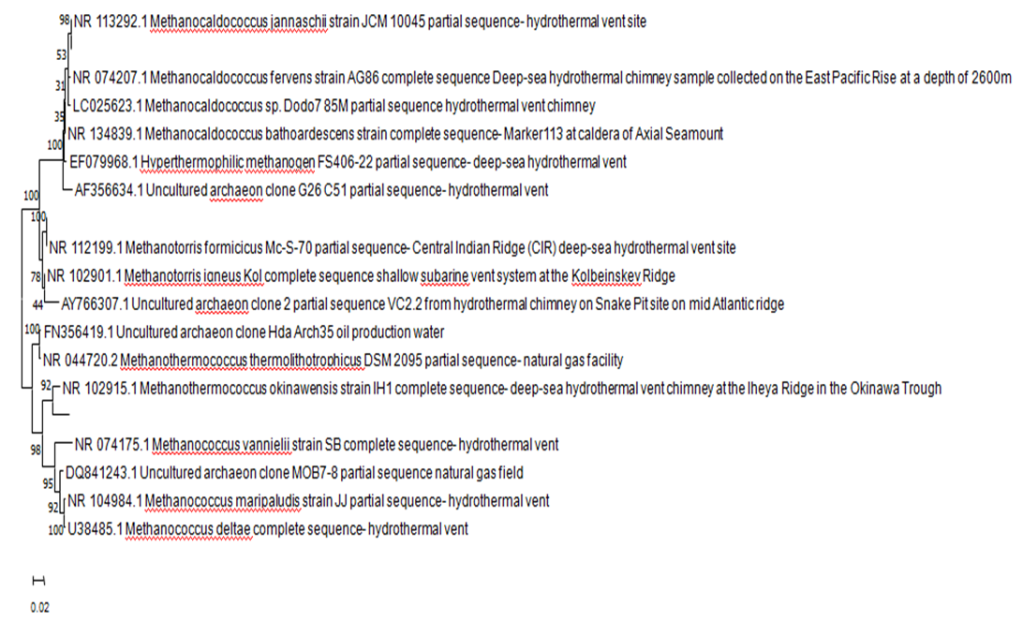

Methanogen Phylogenetic Trees:

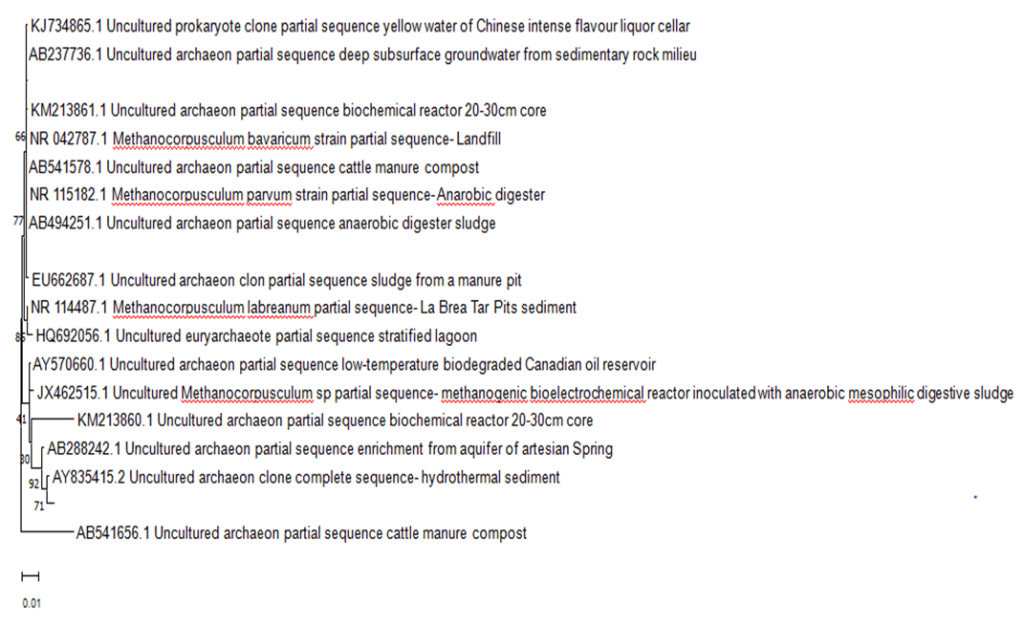

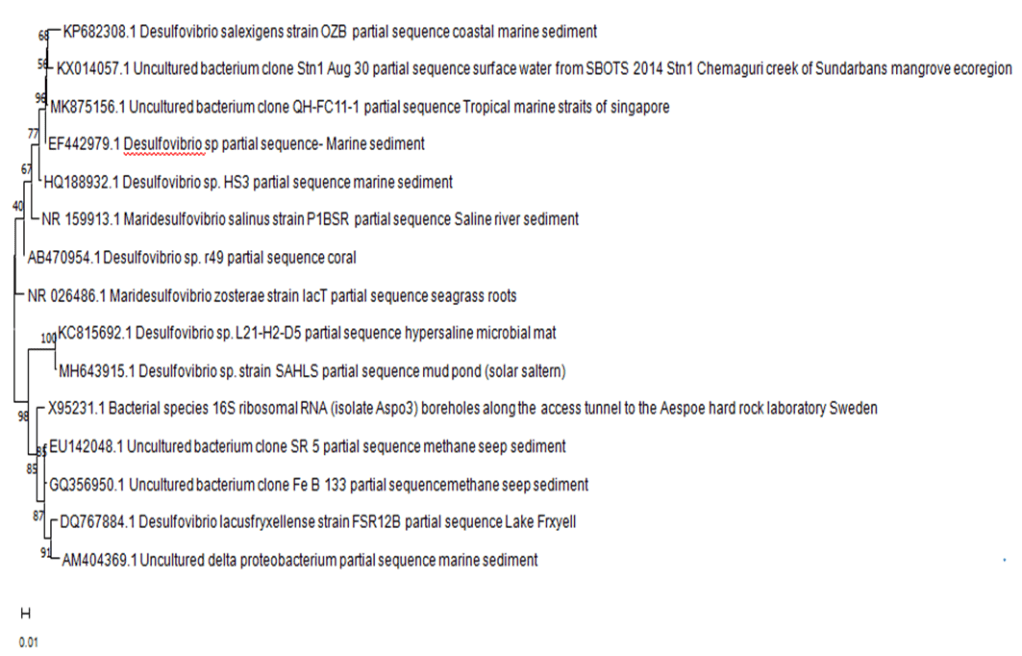

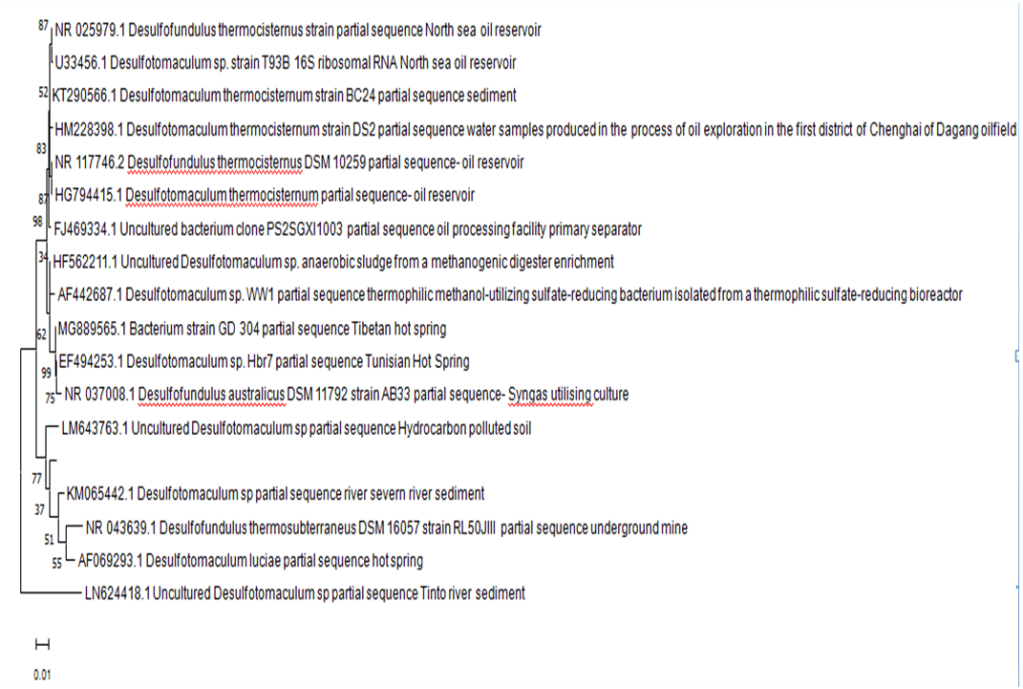

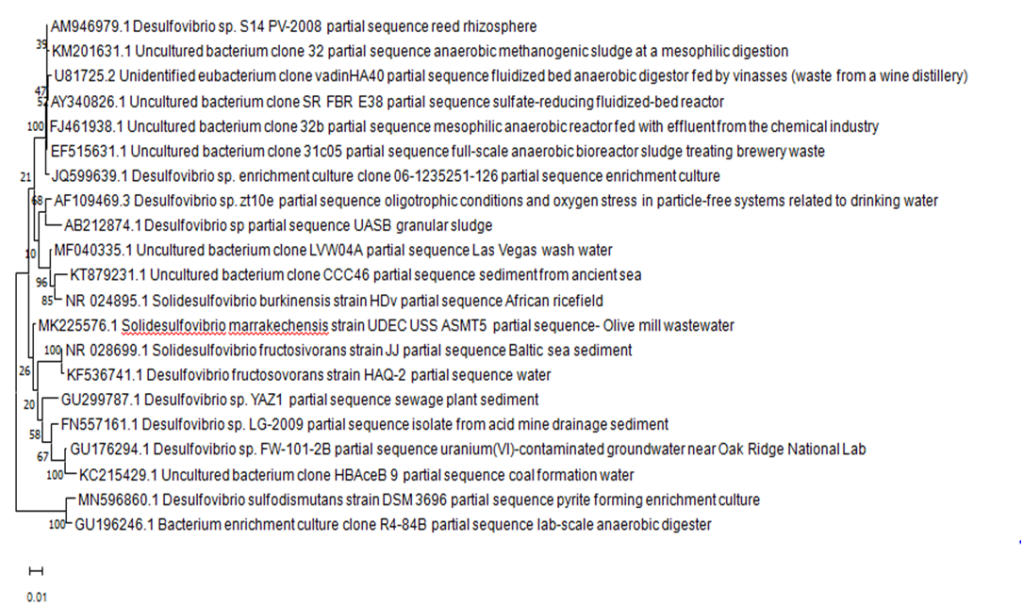

SRB Phylogenetic Trees:

Discussion

The phylogenetic trees confirm the hypothesis that the greater the similarity in the 16S rRNA gene has a large, noticeable impact on what type of environment an organism will inhabit as halophilic organisms share hypersaline environments with other saline tolerant organisms that they have a close 16S rRNA gene. This phenomenon is the same across both methanogens and SRBs and doesn’t change regardless of the variable (temperature or salinity) as both thermophilic organisms and non-extremophile organisms shared very similar environments with each other. This shows that similarities in the 16S rRNA gene can be useful predictor of the tolerances toward temperature and salinity organisms have. This could be advantageous as understanding the tolerances of temperature and salinity is critical for several applications outlined above and currently isolating bacterial species to found out their temperature and salinity is a laborious task which can take time and funding to elucidate. However, as shown by this meta-analysis the more closely two organisms share a 16S rRNA gene the more likely they are to share similar environments so this can be used as a way of approximating whether an organism will be widespread in a particular environment and to what extent they’re tolerant towards temperature and salinity, reducing the need to carry out vast amounts of research to elucidate these tolerances. This should save time and money and will hopefully enable a faster use of the applications described above.

Additionally, not only did the analysis find that similarities in the 16S rRNA gene can give some insights about the environments that organism will be found in and their temperature and salinity tolerances, but it also shows that there is a limited overlap between the environments that extremophiles and non-extremophiles can inhabit. This is interesting and could be a future avenue as to why extremophiles aren’t more widespread in non-extreme environments.

The results of this analysis do appear to broadly agree with the consensus of the scientific literature. The fact that extreme organisms don’t appear to inhabit non-extreme has been shown in the scientific literature. It is important to distinguish between two types of extreme organisms. The first are the extremophilic, organisms that need at least one extreme condition to survive and grow and second are the extremotolerant, organism that are capable of growth in extreme conditions but grow optimally at “normal” conditions. Knowing this, the lack of overlap isn’t all that surprising as extremophilic organisms are characterised based on their need for at least extreme condition in order to survive and hence their distribution within “normal” conditions is understandably small (Rampelotto, 2013). An example of a extremophilic organism is Ferroplasma Acidiphilum, an acidophilic autotroph micro-organism, which requires a large amount of iron, an amount that would prove toxic to most other life-forms and because of this extreme need for iron this organism would prove unable to survive and compete in non-extreme environments. This is one example of an extremophile that would not be able survive in a non-extreme environment (Ferrer et al., 2007).

Further research could focus on the distinction between extremophilic and extremotolerant organisms and elucidate how combinations of extreme temperature and extreme salinity in particular can affect their community structures within ecosystems that host those environmental variables.

There are lots of other potential questions this meta-analysis could help investigate.

Conceptual models:

The conceptual models that are present in most textbooks are supported by only singular species looked at in isolation that have been incubated in a laboratory setting. This can be useful as it sets up the basis of any meta-analysis that may be carried out, but it does little to elucidate how different micro-organisms species interact with each other within a community setting and how this can lead to changes within an ecosystem (like the changes mentioned above). In order to gain a better understanding of community dynamics present themselves between different micro-organisms, an assemblage of all of these studies will need to be compiled to see how different factors impact different species (mainly temperature and pH).

An example of these conceptual methods can be seen below.

The above example illustrates how different organisms can be classified based upon their tolerances towards different environmental factors. The question a meta-analysis could help shed light on by combining the results of the body of scientific literature is how accurate these really are when describing microbial communities. Take the temperature model, for instance. Is it truly the case that there is a gap at 45◦C (at the intersection of the temperature where mesophiles and thermophiles prefer to grow)? If not, a meta-analysis may be able to create a better model that better describes how a microbial community might respond. And if so, what is it about 45◦C that prevents micro-organisms from surviving (with other inputs from pH and salinity) and why hasn’t a microbial species evolved to tolerate this particular combination of environmental factors.

There are a number of ways to represent this graphically

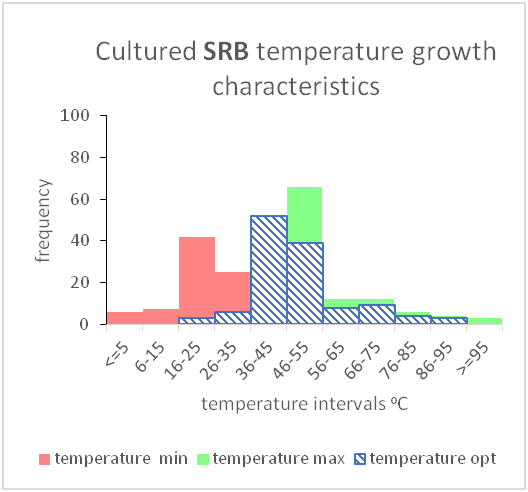

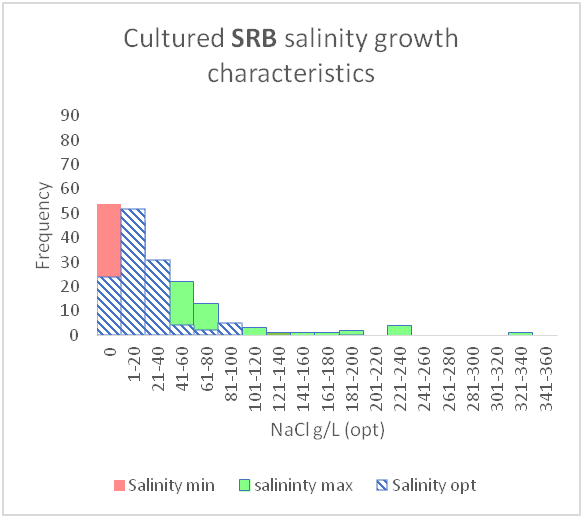

Figure 13- A graph showing the temperature range and the optimal temperature within which growth of cultured sulphate reducing bacteria has been shown

This can be used to show the range for both temperature and salinity and how it impacts growth of certain microbial species

These graphs were produced by my supervisor Neil Gray.

Interdependence of factors:

Another interesting question that this meta-analysis could help answer is how different factors can impact each other. The temperature ranges within which SRBs are capable of growth are not independent of the other factors within the environment. For instance, it could be the case that a SRB is capable of growth within a certain salinity range but as the temperature changes within that environment, their ability to cope with salinity may diminish and this would be important to know due to the wide range of applications mentioned above.

Literature Review:

There is a vast amount of research concerning micro-organisms. This due to two main reasons.

- Firstly, the numerous potential applications that a greater understanding of micro-organisms and how they respond to changes in their environment mentioned above has prompted intense investigation.

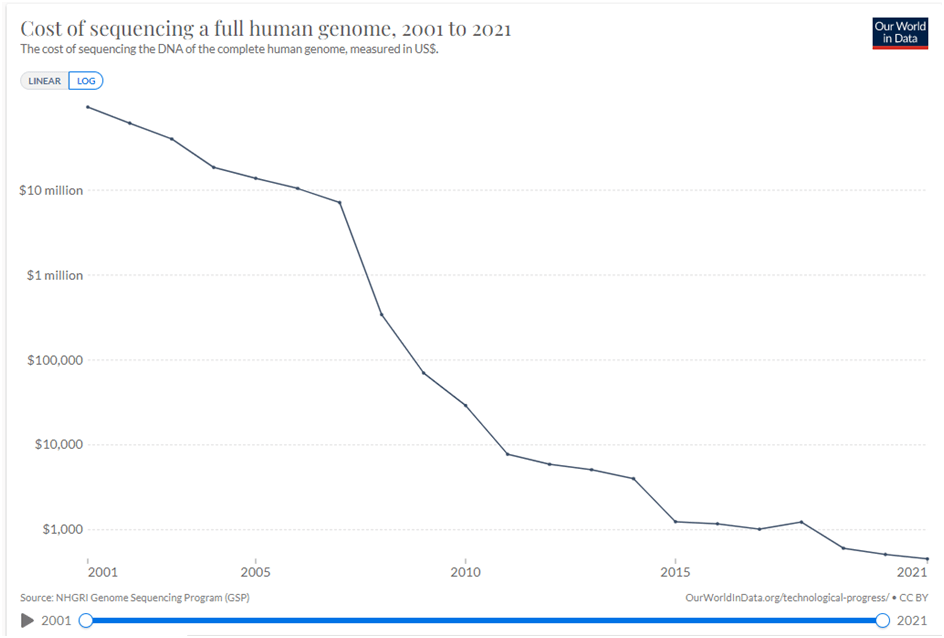

- Secondly, the cost of sequencing has dropped precipitously in recent decades, allowing more research to be conducted cheaper and faster. The cost of sequencing the human genome (using this as a proxy to show overall drop in sequencing costs) has dropped from almost $100 million to about $500 between 2001-2021, shown below (Rosner, 2021).

Due to the vast amount of research concerning microbial communities it is necessary to narrow down the scope of the meta-analysis to include only certain environmental factors, namely temperature and salinity and to also limit the number of micro-organism classes that are investigated, in this case sulphate reducing bacteria and methanogens. The research concerning the temperature and salinity tolerances of sulphate reducing bacteria and methanogens encompasses about 300 studies. This includes 170 research studies for methanogens, 130 research studies for sulphate reducing bacteria. Shown beneath is a sample of the research studies that have been used to determine the tolerance ranges.

As shown above, these can be shown graphically to better represent the temperature and salinity ranges that these organism classes can tolerate.

However, there are gaps in our current knowledge. For instance, as mentioned before, conceptual models seen in textbooks may be giving an incomplete picture by showing gaps between different organism classifications (between mesophiles and thermophiles or between slight halophiles and moderate halophiles). It seems unlikely that there would be such a gap as evolution would produce a species, or a group of species that were capable of tolerating those conditions.

If such a niche gap were to exist, a potential explanation could involve the interdependence between factors, an organism may be able to tolerate a certain salinity range but only at a certain temperature, once that temperature range is exceeded, then that organism may no longer be able to tolerate that salinity range. Organisms can only generate so much energy from their environment based on their metabolisms and adaptations to both high temperature and salinities may require more energy than that organism can reliably generate. Therefore, in order to survive a certain temperature range would require a certain amount energy, which would limit the energy that could be partitioned towards adaptations for high salinity, making surviving in a high salinity environment untenable, explaining the possible niche gap at a certain level of temperature and salinity.

An example to showcase this is taking a species that is a hyperthermophile. It may be the case that the organism devotes so much energy to tolerating high temperatures that it may only be able to exist in very mildly saline and neutral pH environments.

Finally, as mentioned above, the phylogenetic trees showed that extremophiles tend to inhabit extreme environments and non-extremophiles inhabit non-extreme environments. The latter seems intuitive as organisms that don’t have certain adaptations would not be able to survive in environments of very high temperature or salinity, but the reverse seems less intuitive. Why is it that the extreme organisms surveyed in this analysis tended to stay in extreme environments and seemed unable to compete in lesser extreme environments?

Conclusions

In conclusion, the analysis proved two things. Firstly, that organisms that share large areas of their 16S rRNA gene also tend to share similar environments (as far as temperature and salinity are concerned). And secondly, that there is surprisingly little overlap between the environments that both extreme and non-extreme organisms can inhabit. This analysis also provided some interesting future avenues for research. Starting with changing the conceptual models we use and coming with better ways to show graphically what micro-organism communities look like in reality. Secondly, there can be further research that looks at how temperature and salinity interact with each other and how that can impact the community structure of micro-organisms. For example, and mentioned above, an organism may be able to tolerate a certain amount of salinity but only within a certain temperature range and once that range is exceeded the salinity that can be tolerated may in fact change. It could well be the case that temperature and salinity range those organisms can withstand are more flexible than we believe, and they are reliant upon each. Additionally, future analyses could focus on other organism types and other factors. For instance, this analysis only focused upon methanogens and SRBs and temperature and salinity, but further analyses could expand this out and focus on other organism types and how tolerant they are to other variables like pH or nutrient levels. Lastly, this analysis also shows that there is surprisingly little overlap of extreme micro-organisms existing in non-extreme environments which was surprising as there doesn’t seem to be anything about these organisms that should stop them from being to compete sufficiently against other non-extreme organism to be represented within the community structure.