Introduction:

In the wake of the Coronavirus pandemic, the UK’s public finances are not looking particularly healthy at the minute. I’d argue the public finances haven’t looked healthy for a very long time. As a result of this, there has been talk of cutting the foreign aid budget from 0.7% of GNI (Gross National Income) to 0.5%, this would represent a saving of approximately £4-£5 billion annually; although the cut is being floated as a temporary measure. I believe this move would be a grave mistake.

As a side note, it is hardly surprising that foreign aid is the programme that ministers seem to be looking toward for some quick savings. Foreign aid has never been a particularly popular policy for what I think is for two main reasons. Firstly, there is some misinformation associated with the policy. Secondly, there is no major section of the British electorate that the foreign aid budget directly benefits, therefore there is little backlash to proposed cuts despite it being a tiny proportion of overall government spending. This was highlighted in a recent YouGov poll which found that two thirds of British people support the foreign aid cut, compared to under a fifth rejecting the spending cut (YouGov.co.uk, 2020)

I will be highlighting 2 key issues surrounding the foreign aid cut and tackling them one-by- one; the economics and the morality of the foreign aid cut. However, I would like to begin with some background information about current foreign aid spending.

International Development statistics (2019):

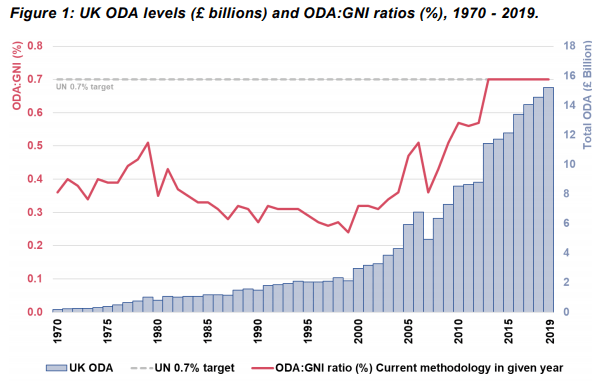

The Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) is a surprisingly transparent government department. In 2019, it released a report detailing how much it spent and how where that money went. Currently, and since 2013, the foreign aid budget is 0.7%; this represented approximately £15.2 billion in ODA (Official Development Assistance) spending in 2019. Figure 1 summarises historical and current levels of ODA spending.

There are 2 main ways this spending is channelled; bilateral and multilateral

Bilateral ODA

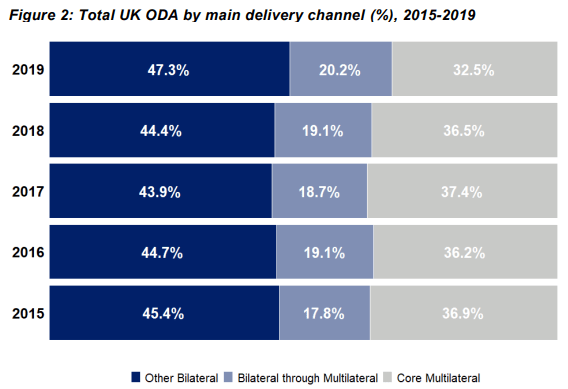

This is usually earmarked spending- the donor has specified where and what the money is to be spent on- this is typically money that is going to be spent in a specific country or programme. Bilateral ODA spending is typically separated into 2 categories. Figure 2 summarises the proportion of ODA spending allocated to each type of spending.

“Bilateral through Multilateral”

This is money that is earmarked to be spent through multilateral organisations. An example of such a multilateral organisation is the World Food Programme’s Emergency Operation in Yemen.

“Other Bilateral”

This ODA money that is spent directly by governments but can include other delivery partners such non-governmental organisations (NGOs), civil society organisations, universities, etc. The delivery of family planning services in Malawi by an NGO would be an example of such ODA.

Core Multilateral ODA

This spending is non-earmarked spending from governments to multilateral organisations. This funding is pooled with other donors’ and allocated as part of the core budget of that organisation. An example of which is the UK’s contribution to the World Bank International Development Association.

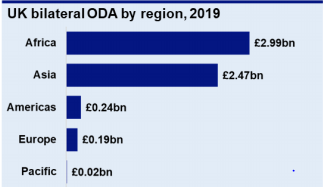

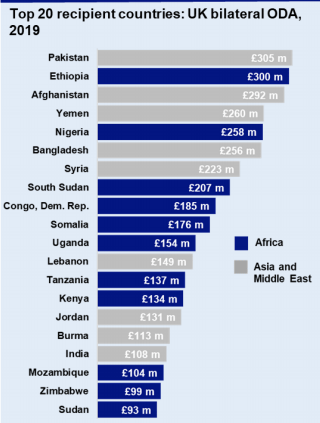

Finally, the bulk of bilateral ODA spending went to Africa or Asia. Bilateral ODA comprises 67.5% of overall ODA spending. Figure 3 below breaks down bilateral ODA spending in 2019 by region. Figure 4 expands on this by showing the top 20 countries by how much ODA spending they received in 2019.

The Economics of the Foreign Aid Cut:

The economics are 2-fold. First I want to contemplate why the cuts are thought to be necessary and then I want discuss what sort of programmes will be cut when we talk about a 0.2% reduction in the foreign aid budget.

But before we delve into the economics of foreign aid, I wish to reveal a bit about my own politics. You will rarely see me supporting continued government spending, and I think the current economic position we find ourselves in will hopefully lead to a discussion about reducing levels of government spending and tax intake. Having said that, we should also be wary of cutting government spending just for the sake of it, especially when that money is supporting many millions of the world’s most vulnerable. Knowing this, I think it’s important to examine which parts of government spending can be cut (which is plenty) without throwing the planet’s most vulnerable off of vital support.

Our Current Economic Situation

As eluded too in my opening remarks, the alleged reason for the need for these cuts is because of the drop in economic activity and the subsequent borrowing that ensued from the pandemic. This is true. As I’ve also said, the public finances haven’t looked healthy for a long time and this latest disaster has done much to exacerbate the already precarious situation we found ourselves in. But again, we need to be careful about recklessly cutting parts of government spending especially when vulnerable people rely on such spending. So let us look at the economic impact of the recent pandemic and examine whether an actual foreign aid cut is really needed and how much help it would actually provide. The situation appears bad; for instance, in the first 7 months of the financial year 2020 (April to October) public sector net borrowing was £214.9 billion, a £169.1 billion increase on the previous year and public sector net debt rose by £276.3 billion over the same time period resulting in an overall stock of debt valued at £2,076.8 billion, which is 100.8% of GDP (the money owed by the public sector is worth more than the value of the UK economy). This was exacerbated by the fact that the UK economy suffered one of the worst economic contractions globally.

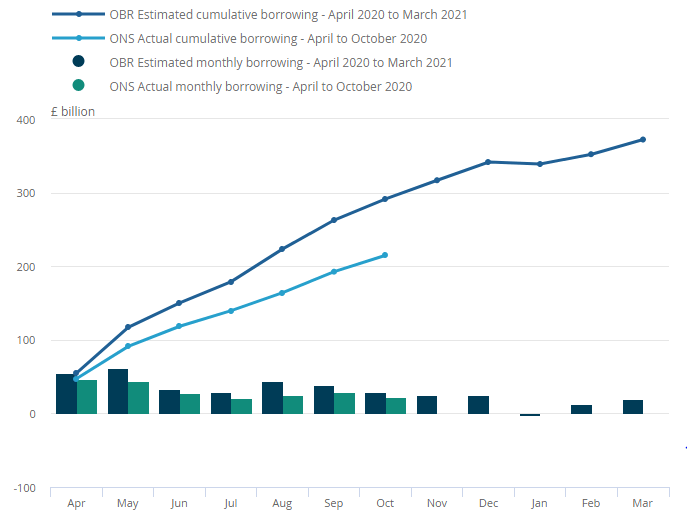

This seems bad, which it is, but not as bad as it may seem at first glance. Firstly, the interest rate at which the UK government can borrow money is at historic lows, meaning the government can borrow money very cheaply. For example, a UK government bond with a maturity of 20 years has a yield of 0.83% (as of December 2020). Secondly, the ONS is consistently revising down projected government borrowing. Figure 5 shows projected and actual government borrowing from April to October 2020. It shows that actual borrowing is consistently lower than projected borrowing.

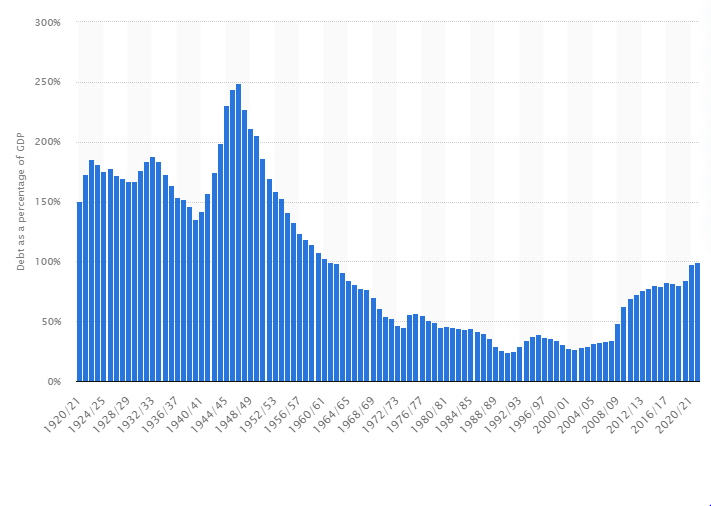

Furthermore, the percentage of debt to GDP is hovering around 100% currently. While this is not good, it peels in comparison to what it has reached historically. Figure 6 shows historic levels of debt to GDP percentages. The position we find ourselves is not unique in our history.

The GDP contraction experienced because of the pandemic and the lockdown restrictions had a considerable impact on the economy. However, there has been strong growth and the economy seems to be rebounding quickly. The latest ONS data (April 2021) shows that GDP is just 3.7% below February 2020, showing strong growth as lockdown measures are eased. All this is to say that whilst the economic data seems gloomy at first glance, it is not as bad as first feared and cutting £4 billion to the world’s poorest will do little to remedy our situation.

What exactly will be cut?

The second component of the economics of the foreign aid cut I wish to highlight is what exactly a 0.2% cut in the foreign aid budget will entail. The cut to foreign will lead to about £4 billion worth of cuts to the foreign aid spending and I think it’s important to look at exactly what this means. The list below shows some examples of the type of cuts that have been proposed to accomplish the 0.2% reduction (some of these cuts are already being implemented) (Devex, 2020):

- The U.K. cancels support for the far-reaching Strategic Partnership Arrangement with Bangladesh. The decision means the U.K. will no longer provide an education for 360,000 girls, school places for 725,000 children, nutritional support for 12 million infants, access to family planning services for 14.6 million women and girls, skills training and assets for 385,000 families in extreme poverty, or climate interventions for 2 million households.

- The Malawi Violence Against Women and Girls Prevention and Response Programme has been cancelled, according to a source working at one of the implementing organizations.

- A 42% reduction in funding to the Rohingya crisis response.

- 60% reduction in funding to UN Women.

- 60% cut to funding to UNICEF.

- 83% cut to UNAIDS

- 90% cut to Neglected Tropical Diseases funding (I find this particularly egregious given the year we’ve just experienced).

- 85% funding cut to the United Nations Population Fund.

- 95% funding cut to the Global Polio Eradication Initiative.

Knowing that a £4 billion cut in foreign aid will do little to remedy the UK’s financial situation and knowing that the cuts mentioned above will lead to a real and significant lowering in the wellbeing of the world’s poorest and most vulnerable, I think rethinking our decision to cut foreign aid is a smart move.

The Morality of the Foreign Aid Cut:

I appreciate you may be thinking it’s weird that I am talking about morality on a science blog but I disagree. I believe that the scientific method, rationality and logic are all tools that can (and should) be used to advance human flourishing. In this case, we should look at the economic data and weigh up whether cutting the programmes stated above and others like it is worth it in order to achieve a reduction in government spending. I don’t believe it is.

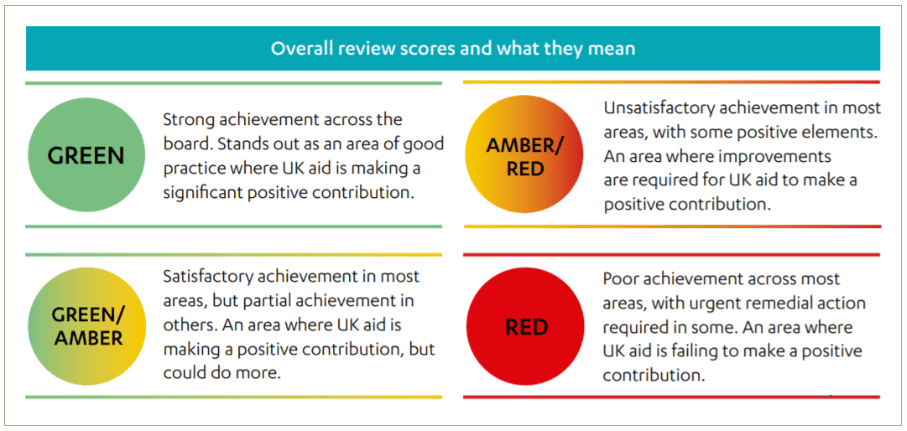

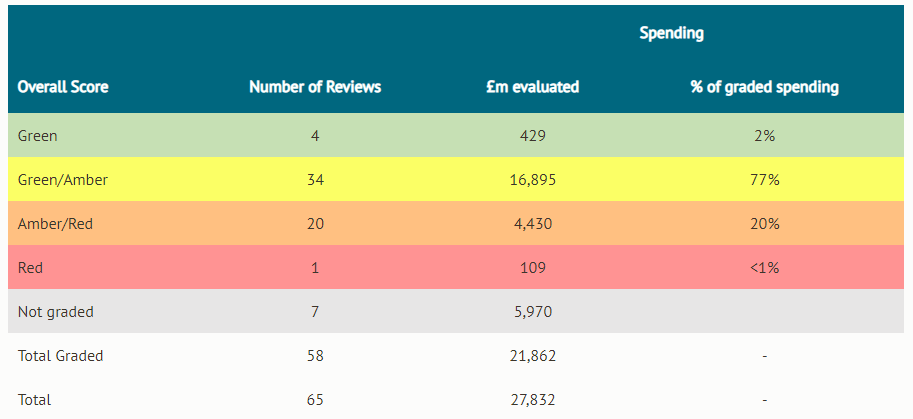

Furthermore, whilst we’re discussing using the scientific method to advance human wellbeing I think now is a good time to actually evaluate how much value for money we get from our foreign aid spending, as there seems to be this idea that foreign aid is mostly wasted, or is even counter-productive. The Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) is a remarkably transparent government department with projects been independently assessed for efficacy by 3rd parties. For example, The UK is one of the few countries to independently scrutinise its aid spending. This is done through the Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) which is an independent body reporting to Parliament. The ICAI assesses aid programmes and releases a report and the Centre for Global Development aggregated all these reports. Overall, 79% of all aid programmes where found to have a positive impact with only 20% needing significant improvement. This can be seen in figures 7 and 8 shown below which show the grades achieve by different foreign aid programmes.

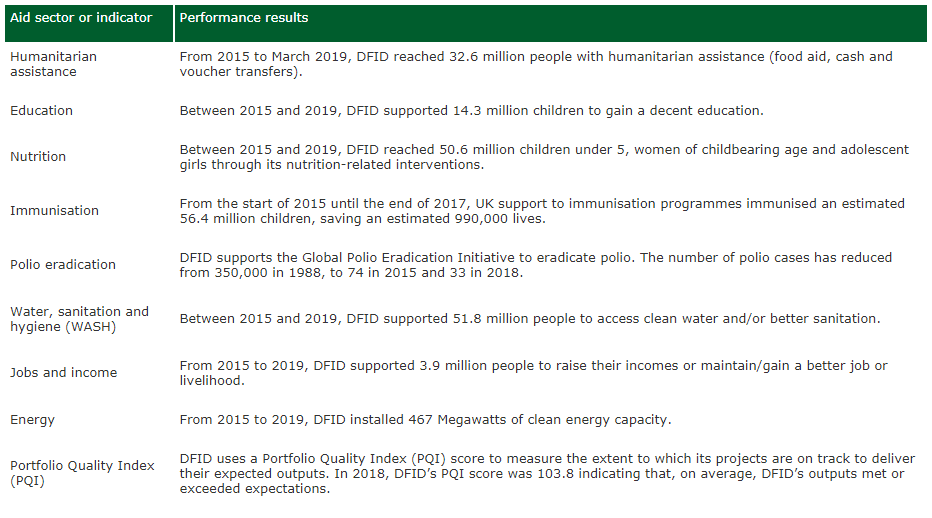

This dispels the common myth that foreign aid is usually wasted money or counterproductive. Additionally, I would like to point to some direct benefits that have been accomplished with our current foreign aid spending (figure 9).

Conclusion:

In conclusion, the government should not cut the foreign aid budget because of supposed budgetary constraints. As shown above, the UK economy is likely to rebound strongly and actual borrowing is consistently lower than projected borrowing, showing that the gloomy economic data is not as bad as it first appears. Also a 0.2% reduction is unlikely to remedy our situation but will cause grave harm to people in the developing world. Furthermore, as far as government spending goes, the FCDO is a remarkably effective and transparent department with much of their spending openly scrutinised by 3rd parties. Additionally, much of this scrutiny has revealed that 79% of UK foreign aid spending is having an overall positive impact on people’s lives. There is one reason why the government is cutting foreign aid; they need to be seen to be doing something with all the gloomy economic data that’s been released but can’t afford to cut programmes/government spending that would actually make a meaningful difference in lowering spending. Instead they’ve opted to slash away at a policy that constitutes less than one percent of the budget and despite the fact it has an overwhelmingly positive impact on the world’s poorest. They’ve done this because it’s the easy thing to do, despite the lives that will be lost. I, for one, find that morally despicable.