The following blog post is my dissertation that was submitted as part of my 3rd year scientific project submission. It is a scientific overview of the scientific literature that was available at the time of writing (submitted on April 30th 2021) concerning Martian methane. The report delves into the research concerning the discovery on Mars, possible generation and storage mechanisms (both biogenic and abiogenic), possible methods to ascertain whether said methane is biologically produced or not and possible future missions to Mars.

Abstract:

The purpose of this dissertation is to provide an overview of the existing literature concerning Martian methane and to critically appraise this research to attempt to ascertain its origins, its sinks and then to provide comment as to what future missions to Mars should focus on to be of the greatest benefit to understanding the origins of methane on Mars.

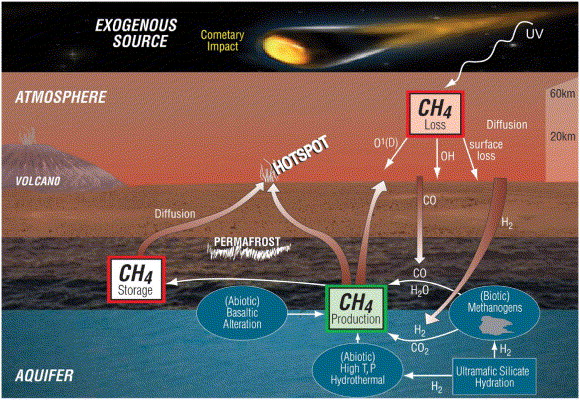

Methane is the focus of this review- as 90% of all terrestrially produced methane is biological (Zahne et al, 2011). Methane on Mars is shown to have a spatial-temporal variation which has suggested the presence of localised sources or localised sinks (Jensen et al., 2004). There are several hypothesises concerning the production including Methanogenesis, serpentisation, volcanic activity, and the introduction of methane from exogenous sources (see figure 1 for a summary). The-exogenous sources hypothesis has been met with widespread criticism as it doesn’t account for the spatial-temporal variation of methane observed in the Martian atmosphere. Likewise, with the amount of methane needed to produce a background level of 10 ppvb being calculated at an output of between 126 tonnes (Atreya et al., 2007) and 270 tonnes (Chastain and Chervier, 2007); it is unlikely such a mechanism could produce the quantities needed, particularly when you’d expect between 100-1,000 times the amount of SO₂ to also be produced simultaneously, a gas whose presence hasn’t been confirmed in the atmosphere (Encrenaz et al., 1991, Encrenaz, 2000). This means the two most likely scenarios currently are sub-surface Methanogenesis and serpentisation of olivine bearing rocks.

Future missions principally The Rosalind-Franklin Rover and The Perseverance Rover missions will prove invaluable particularly through increasing our understanding of the Martian geology, which is critical when exploring the impact that post-genetic alterations may have on methane as it moves through the Martian regolith which will be vital in determining the (a)biogenic nature of Martian methane (Etiope, 2018).

Introduction:

Methane on Mars was first detected by Krasnopolsky et al, 2004, and was later shown to vary in both its spatial and temporal distribution in the atmosphere. There has been much speculation about potential generation pathways for methane on Mars. These potential pathways include, but are not limited to, methanogens existing in small colonies in the Martian sub-surface, to serpentisation of olivine-bearing rocks and UV photolysis of organic matter. However, subsequent readings made by the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO) have so far failed to detect methane in the Martian atmosphere despite more sensitive instrumentation (Korbalev et al,. 2019). This loss could not have taken place through known conventional removal processes such as oxidation or UV photolysis as these pathways are believed to take centuries compared to the breakdown observed on Mars taking place over years. This has led to hypothesises about potential methane sinks that exist on, or within the, Martian surface that could account for the fast-paced loss of methane. These hypothesises include a reaction of methane with eroded quartz grains on the surface (Jensen et al., 2014), or the adsorption of methane onto the Martian soil (Gough et al., 2010), or the presence of strong oxidisers on the surface, like hydrogen peroxide (Atreya et al., 2007).

Whether the methane observed on Mars is the result of biological processes (sub-surface Methanogenesis) or through abiotic processes (serpentisation of olivine) is still unknown. Some ways of determining this include analysing isotopic composition by measuring isotopes of ¹³C/¹²C, with ¹²C being favoured by biological organisms and ¹³C usually being more indicative of abiotic processes. Another way includes looking at methane/ethane ratios within the atmosphere. A high methane/ethane ratio is suggestive of biological activity, whilst a low ratio suggests a non-biological pathway (Etiope, 2018). And finally looking at isotopologues could provide insight into the origins of methane. ¹³CH₃D can be useful in helping to differentiate between high temperature thermogenic methane and magma-derived gas. However, these methods have flaws associated with them and these data need to be critically analysed and from this analysis, improvements can be made to the platforms that will be used in the future to gather information about the origins of methane observed on Mars.

Methane on Mars, a contradiction:

Early observations that took place in 2004 showed that methane was present in the Martian atmosphere. For example, Krasnopolsky et al, 2004, used the Planetary Fourier Spectrometer (PFS) to take readings of the Martian atmosphere and observed a methane concentration of approximately 10ppb (parts per billion), plus or minus 3ppb. A similar concentration was also recorded that same year by Formisano et al, 2004 who observed a concentration of 10ppb, plus or minus 5ppb. These two studies are the earliest observations of methane within the Martian atmosphere but are by no means the only examples. (Krasnopolsky et al., 2004, Formisano et al., 2004)

In addition to these early studies, there have been numerous confirmatory studies that have also detected methane within the Martian atmosphere, albeit in differing concentrations. Figure 2 shows a summary of different research teams and their observations of methane. This observation also coincided with in-situ observation by Curiosity Rover. (Krasnopolsky, 2007. Zahnle et al., 2011. Guiranna et al., 2019).

Recorded Methane Observations:

| Research study | Methane concentration recorded |

| Krasnopolsky et al, 2004 | 10ppbv (+/- 3ppb) |

| Formisano et al, 2004 | 10ppbv (+/- 5ppb) |

| Krasnopolsky, 2007 | 3-10ppbv |

| Mumma et al, 2009 | “extended plumes” in 2003/2006 |

| Zahne et al, 2012 | <8ppbv |

| Guiranna et al, 2019 | 15.5ppbv (+/- 2.5ppb) |

Due to these findings showing methane being present within the Martian atmosphere, more sophisticated equipment has been utilised to try and ascertain more precise concentration measurements. This was done through the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter (TMO) which has instrumentation which 10-100x more sensitive than the instruments that have been used in previous observations, however, the TMO has yet to find any methane in the atmosphere despite the much more sensitive equipment present onboard (Korablev and Vandaele, 2019). This poses two potential scenarios; first is that the previous observations were incorrect. But due to the substantial amount of literature that has confirmed the presence of methane in previous years the other scenario, that an unknown process has caused the rapid loss of methane from the Martian atmosphere, is the running assumption until further counter evidence is presented.

The potential origins of Methane:

The majority of methane produced on Earth is produced through Methanogenesis, an anaerobic process (Lessner, 2009). This process is carried out by methanogens which are known to occupy landfills, ruminants, termites, and the anoxic environment of soils beneath the seafloor (Serrano-Silva et al., 2014). Rice paddies are also shown to produce methane during plant growth (Sirohi et al., 2010). This means that methane could be evidence of life on Mars. However, biogenic production is only one of many potential causes of Martian methane. There are multiple potential abiogenic sources that could account for observed methane. These potential sources include olivine serpentisation (Max and Clifford, 2000, Oze and Sharma, 2005), asteroid impacts (Keppler et al., 2012), degradation of methane clathrates (Chastain and Chevrier, 2007), volcanic activity (Encrenaz et al., 1991, Encrenaz, 2000), and wind abrasion that releases bonded methane from eroded quartz grains in the Martian soil (Safi et al., 2019).

Due to the observed concentrations of methane and assuming a methane life time of 2×10^10 s, a flux of 1×10^5 molecules cm-2 s-1 is required to explain a methane mixing ratio of 10ppb, which has been observed before, this implies a disk averaged source strength of 126 metric tonnes annually (Atreya et al., 2007). However, there isn’t a consensus on this figure as seen in Chastain et al, 2007 who estimated an emission of upto 270t is required to maintain atmospheric concentrations. (Chastain and Chervier, 2007). This is very useful information as now a basis can be formed with which to judge the aforementioned sources to see if it’s theoretically possible for them to be responsible for the observed concentrations of methane observed in the Martian atmosphere.

Methanogenesis:

Methanogenesis is the biological process of producing methane. This is carried out on Earth in part by subterranean and oceanic chemolithotrophic microorganisms as part of their metabolism, but as mentioned previously, methane can also produced by methanogens in the digestive tracts of ruminants and termites along with bacteria that reside in the soils of rice paddies. This chemical process can occur one of two ways:

4CO + 2H2O ➡ CH4 + 3CO₂

Or

4H2 + CO2 ➡ CH4 + 2H2O

Figure 3- The two potential reaction pathways possible to produce biological methane (Atreya et al, 2007).

It is hypothesised that microbial colonies could exist in aquifers beneath the permafrost on Mars and they’d be able to utilise CO (700ppmv) and H₂ (40-50ppmv) that has diffused through the regolith into the aquifers to fuel their metabolism and released methane as a by-product (Atreya and Gu, 1994). If the methane is indeed of biological origin (produced by methanogens) then the microbial colony would need to be fairly small due to the relatively low concentrations of methane observed. There may also exist organisms that utilise this produced methane as an energy source as well (Methanotrophs). This would provide another mechanism by which methane could be removed from the atmosphere. This method could also be used to explain the spatial variation seen in the methane observation, which other methods cannot fully explain (Atreya et al., 2007).

Serpentisation

Serpentisation of olivine bearing rocks is a potential source of abiogenic methane. Serpentisation refers to the process by which a rock is changed through the addition of water into its chemical structure. It works chemically quite similar to Methanogenesis as serpentinisation of olivine bearing yields hydrogen which then reacts with carbon-bearing species (this includes carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide and formic acid) to yield methane.

Hydration of ultramafic silicates (olivine/pyroxene) results in the formation of serpentine and molecular hydrogen

(Mg, Fe)₂SiO₄+H₂OàMg₃Si₂O₅(OH)₄+Mg(OH)₂+Fe₃O₄+H₂ (aq)

Olivine/pyroxene + water àserperntine + brucite + magnetite + hydrogen

CO2 (aq)+[2+(m/2n)]H2 (aq)→(1/n) CnHm+2H2O

CO2 (aq)+4H2 (aq)→CH4+2H2O

C+2H2 (aq)→CH4

Figure 4- The reaction pathway required to produce methane from geologic hydrogen (Atreya et al, 2007).

The H₂ (aq) produced during serpentisation reacts with carbon grains or CO₂ of crustal rocks to produce methane and other higher order hydrocarbons in decreasing abundances. (Atreya et al., 2007). Laboratory experiments simulating temperatures and pressures of 390⁰C and 400 bar, a relatively large production of methane using the above pathway was found catalysed by Fe-Cr oxide (Foustouskos and Seyfired, 2004). However, it is unknown as to whether this could occur on Mars as black smoker type temperatures are expected to be reached between 25-50km below the surface where liquid water is unlikely to be stable and the above reaction requires an aqueous phase (Oze and Sharma, 2005). It is also unlikely for any produced methane to escape into the atmosphere due to the great depths it would have to travel through (Atreya et al, 2007).

Feldman et al, 2004, mapped a large concentration of hydrogen close to the Martian surface using the Odyssey spacecraft, showing a reservoir of hydrogen that could react with CO2, a major constituent of the Martian atmosphere, and produce methane (Feldman et al., 2004).

Research shows that there are olivine-rich volcanic rocks present on Mars and that olivine is a major constituent of Martian sediment (Hamilton and Christensen, 2005). In addition to this, there is lots of research showing extensive water-rock alteration on Mars, this is seen through widespread observation of hydrated silicates in the Martian crust. Including this, Martian meteorites also show signs of extensive aqueous alteration including serpentisation. And orbital measurements, using MRO-CRISM, suggest olivine serpentisation occurred at some point in the past and that this could be extensive. (Mustard et al., 2008, Noguchi et al., 2009, Wray and Ehlmann, 2011, Ehlmann et al., 2010, Fisk and Giovannoni, 1999). So, it is known that serpentisation reactions have the capacity to occur widespread right now and we have evidence to suggest that suggest reactions have occurred extensively in the past. Along with this, computer modelling shows that low-temperature serpentisation reactions have the capacity to yield more than enough methane to explain observed concentrations. For instance, it has been shown that as much as 10^15 tons could be produced through basaltic alteration (Wallendahl and Treimann, 1999). Alternatively, if this serpentisation occurred historically, then the methane that was produced could have been stored in methane clathrates and slowly raised to the planet’s surface. The rate of release is unknown but the mechanism could produce 200,000 tonnes annually which is 1,000 times more than the 200 or so tonnes needed to maintain observed methane concentrations which comfortably accommodates a slow or non-uniform release (Max and Clifford, 2000).

Methane has been shown to not only vary over time but also to vary across space as well. Oze and Sharma, 2005, suggest that this spatial variability would suggest a localised sub-surface source and that production of methane through serpentisation could fit in with what the current literature says about the spatial distribution of methane in the Martian atmosphere (Oze and Sharma, 2005).

Exogenous Sources:

Exogenous sources include meteorites, comets, and interplanetary dust particles. There is a lot of scepticism in the scientific community as to whether the role of exogenous sources could play a role in the observed concentrations found in the Martian atmosphere. Micro Meteorite dust is unlikely to be a major source as most of it is oxidised by the atmosphere (Flynn, 1996) and the input of meteorites is also likely to be negligible (Atreya et al,. 2007).

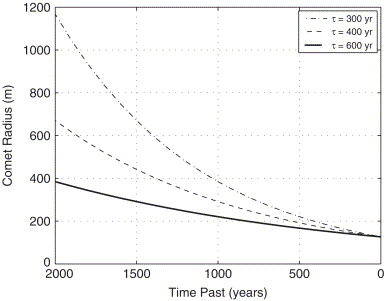

Comets could be a potential source. Assuming that any source of methane that come from a comet impact will have declined to levels of 2.2×10^15 cm^-2 CH₄ molecules (10ppbv) and assuming an average of 1% methane by weight of the Oort cloud comets (Gibb et al., 2003) and assuming a methane lifetime of 600 years (upper range of current photochemical models), it’s possible that an impact by a comet with a radius of 130 metres as recently as 100 years ago to a comet with a radius of about 360 metres as long ago as 2,000 years ago could be enough to supply the required methane to account for the 10ppbv concentrations observed (Atreya et al., 2007.,see figure 5 for an illustration). The possibility of such an impact having occurred in the recent past cannot be ruled out; however the spatial variation in methane detection remains difficult to explain. Even if the methane was supplied by much smaller but more frequent cometary impacts the same issue would still arise as the time for methane to be distributed across the whole planet surface is months. If localised and highly effective methane sinks were to exist on the surface that could remove this methane then this explanation could be plausible.

Keppler et al, 2012, also notes that the input of methane from ablation of carbonaceous meteorites during entry to the atmosphere is most likely negligible. However, they do put forward the idea that UV-radiation-induced methane formation from meteorites could explain a significant fraction of the methane observed on Mars. They show that methane can be produced in large quantities from the Murchison meteorite when it is exposed to UV radiation and under conditions similar to those found on Mars. Some research suggests that meteors containing significant amounts of organic matter do reach the Martian surface (Flynn and McKay, 1990) and that this organic matter can be converted into methane when exposed to UV radiation (Keppler et al., 2012). An incoming meteorite influx of 2,700 tonnes to 59,000 tonnes (with organic matter at 2% of weight) contains between 54 tonnes to 1,180 tonnes of Carbon. Assuming a conversion of 50% of this organic matter to methane then between 8 tonnes to 787 tonnes of methane could be produced (Within the 126 tonnes to 270 tonnes estimated to be required for 10ppbv). However this explanation still doesn’t account for the temporal or spatial variation seen in the literature.

Figure 5- comet radius (m) and time of impact (years) accounting for different methane lifetimes (Atreya et al, 2007). The comet would need to deliver a set amount of methane that would degrade to current observed values of 10ppbv.

Volcanic Activity:

Much like exogenous sources, there is much scepticism around the role that volcanic activity plays in the role of methane on Mars. Firstly, volcanic activity plays a minimal role of methane production on Earth; only about 0.2% of methane produced on Earth comes from volcanic activity. Whilst Earth and Mars are clearly for different systems, the minimal role that volcanic activity plays on terrestrial methane can give some indication of methane production on Mars (Paul, 2017). In addition to this, we can analyse fumarolic gas content and we find that sulphur dioxide is 100-1,000 times more abundant than methane, meaning that if we assume that fumarolic gases are similar in composition between Earth and Mars and that volcanic activity was responsible for a significant fraction of the methane found on Mars then we’d also expect to see sulphur dioxide to be about 100-1,000 times more abundant than methane and the literature doesn’t support this. For instance, if a methane concentration of 10ppbv was assumed and all of this had originated from volcanic activity, there’d be an expected concentration of 1-10ppmv of SO₂; however SO₂ hasn’t been detected in the Martian atmosphere. Only an upper limit of 3×10−8 for SO₂ has been derived by ground and space-based observations (Encrenaz et al., 1991, Encrenaz, 2000).

Where did all the Methane go?:

The process of methane being destroyed or removed from the atmosphere is not surprising, after all methane on Earth is routinely oxidised into carbon dioxide, what is surprising is the time frame that the removal has taken place over, it happened over years as opposed to centuries. Some research has looked into the destruction of methane within the atmosphere. There are two primary pathways that we expect methane to be removed, oxidation in the lower atmosphere and photolysis in the middle and upper atmosphere. Wang et al noted that the observed destruction of methane happened at a speed far faster than would have been expected from photochemical models (removal was observed within 4 years). Bertaux et al, 2012, suggested that the main factor influencing methane removal from the atmosphere was vertical column mixing but the recycling rate of the upper atmosphere is too slow to significantly reduce the lifetime of methane in the Martian atmosphere, which they found to be around 340 years (Wang et al., 2010). This suggests an unknown process, or multiple processes, that are impacting the lifetime of methane within the atmosphere.

There are multiple methods that have been hypothesised to be responsible for the removal of methane. The first of these potential methods is the reaction of methane with quartz grains that have been eroded by Martian winds. This is supported by Jensen et al, 2014, that carried out tumblry experiments that were-designed-to-mimic-the-wind-erosion-of-quartz grain. These-grains-were-then-analysed using Solid-State Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) and found that methane had reacted with the eroded surface to form covalent Si-CH₃ bonds which are stable at temperatures of up to 250 degrees Celsius (Jensen et al., 2014). This method could work in tandem with the recent findings of Safir et al, 2019, which suggests that methane can be released by through Aeolian abrasion of Martian particles. It could be the case that this phenomenon works in both directions, methane is capable of reacting with Si-grains and the Aeolian abrasion can work as a releasing mechanism for this trapped methane (Safir et al., 2019).

A second proposed method of fast removal of methane from the atmosphere was proposed by Gough et al, 2010. They report that it may be possible for methane to be adsorbed onto the Martian soil. This can be used to explain the temporal and spatial variability in the reported observations of methane as this method usually occurs on a seasonal time scale. However, this method is unlikely to explain the quick loss of methane observed by TMO as this method can only sequester methane for short time frames, while the loss observed on mars appears to have taken place over multiple years (Gough et al., 2010).

A final mechanism that could be responsible for the removal of methane is the presence of a strong oxidiser. This is proposed by Atreya et al, who suggested the oxidiser could be hydrogen peroxide which is known to be produced in dust storms that are a common occurrence on Mars. This is proposed because the loss of methane due to photolysis and oxidation are too slow to account for the observed losses but there is a possibility of heterogeneous loss to the surface, usually this process would be slow and would therefore not impact the methane lifetime on Mars significantly (Atreya et al, 2007). However, if the surface were reactive then this would speed up this loss and hydrogen peroxide could be responsible for this, especially after the presence of the oxidiser was confirmed in 2003 at concentrations of 20-40ppb (Encrenaz et al., 2004).

Methane Clathrates:

Chastain et al, 2007, suggests that thermodynamic conditions on Mars could allow for gas clathrate deposits to exist at the polar ice caps and in some areas of the planetary subsurface. Three things are needed for methane clathrates; methane, water and an appropriate temperature/pressure combination. Both methane and water are thought to exist on Mars; water was shown to exist in the polar ice caps that persist after the annual sublimation of CO2. (Kargel and Lunine, 1998). In addition to this, there is data from satellites (Mars Odyssey and Mars Express) that shows water in the Martian subsurface and in the Northern Ice Caps (Milliken et al., 2006. Langevin et al., 2005). Considering the thermodynamic properties of the crust and permafrost regions with a density of 2,500 kg/m^3, it is possible for clathrates to be stable at depths as shallow as 15 m beneath some permafrost areas and could have a thickness of 3-5 km at the equator and 8-13 km at the poles, although depending on conditions, the clathrates could stable at much shallower depths, even as low as 2.7 m (Max and Clifford, 2004). 1 m^3 of methane clathrate can hold about 164 m^3 of methane which is equal to about 116 kg of methane. This means that a 1 m thick clathrate with an area of 2,230 m^2 could account for the 270 tonnes of methane needed to account for observed methane concentrations. Clathrates are known to exceed 100 m thickness on Earth (Dallimore et al., 2003). This shows that the methane that was observed on Mars doesn’t necessarily need a current source. Alternatively, methane producing mechanism(s) may have occurred centuries ago and the resultant gases could have been stored and released at a later date. Anything that causes a temperature increase or reduces the lithostatic pressure of an area could cause the destabilisation of a clathrate. Examples of potential mechanisms that could cause the destabilisation of a clathrate are numerous. Firstly, small-scale pitting or mass transfer due to a seismic event could cause clathrate destabilisation (Milton, 1974). Secondly, small impactors could also have a similar effect, a crater with a diameter of 16 m could excavate 1,000 m^3 of material causing both a reduction of lithostatic pressure and shock-heating of the underlying strata of material (Knapmeyer et al., 2006). And finally, climate change could cause a general increase in the global temperature on Mars and thus, cause the destabilisation of shallow methane clathrates. The climatic change could be brought about by changes in the axial tilt of Mars. It is proposed that Mars is entering an interglacial period that is causing the retreat of ice-rich deposits polewards which could potentially cause the release of the trapped methane from clathrates. Gainey and Madden, 2012, suggests that near surface methane hydrate reservoirs could be a feasible source of the methane plumes observed by Mumma et al, 2009 (Gainey and Madden, 2012).

Biogenic or Abiogenic?:

There are several ways to ascertain whether the origins of Martian methane are (a)biogenic.

Isotope Composition:

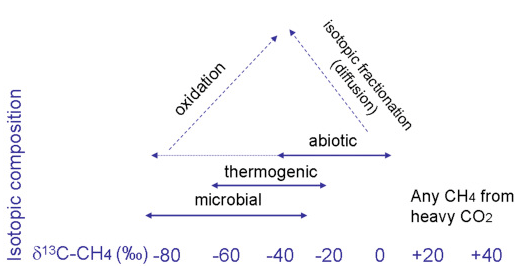

It is possible to ascertain the origins of Martian methane by examining its isotopic composition. Methane on Mars can come in two different types of Isotopologues. Nair et al, 2005, notes that it’s possible to differentiate between terrestrial methane sources by measuring the relative abundance of three common isotopologues (CH₄, CH₃D, ¹³CH₄). Such a differentiation may also be possible when it comes to attempting to differentiate between biogenic and abiogenic sources (Nair et al., 2005). The understanding of the origin of Martian methane will require numerous complementary methods including in-situ observation along with remote sensing and laboratory work. Three main instruments; Quadrupole Mass Spectrometre (QMS), Gas Chromatography (GC), and Tunable Laser Spectrometre (TLS) make up the SAM analytical chemistry suite on NASAs Mars Science Laboratory mission. This suite has the capability of measuring absolute methane concentration (ppt) and the isotopic concentrations of a variety of trace gases. The TLS, in particular, will investigate the isotopic composition of methane (¹³C/¹²C and D/H). Measurements near the MSL landing site will be correlated with satellite (Mars Express, 2016) and ground-based observations (Webster et al., 2011). Finally methane that is enriched in ¹²C could be indicative of microbial activity, as biological organisms have a preference for lighter isotopes, while ¹³C enriched methane is more indicative of an abiotic gas. The NOMAD spectrometer suite of the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO) will have the capability of measuring important parameters that will illuminate the origins of Martian methane including stable C isotope composition, its isotopologue ¹³CH₃D, and ethane concentrations (Etiope, 2018).

Methane/Ethane Ratios:

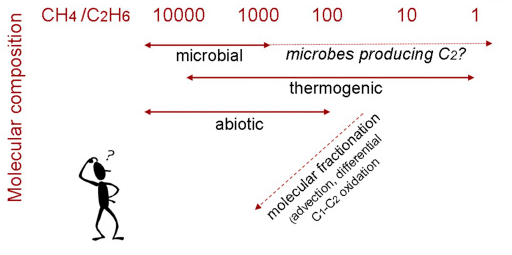

In addition to analysing the isotopic composition of methane to investigate its origin we can also analyse the proportion of methane to other higher alkanes in the Martian atmosphere. Etiope, 2018, also noted that a high methane/ethane ratio would be indicative of a biogenic source of methane and the NOMAD suite aboard the ExoMars TGO will also be capable of analysing the Martian atmosphere for the abundances of these gases (Etiope, 2018). In addition to this, Tazaz et al, 2013, also confirms this by saying that biogenic methane production is not usually accompanied by ethane production. This further reinforces the idea that a high CH₄/C₂H₆ ratio would be indicative of a biogenic methane source. They suggest that a methane/ethane ratio of above 1,000 suggest a biogenic source whilst a ratio of under 50 is likely to suggest a thermogenic (thermal degradation of organic matter to yield methane) source (Tazaz et al., 2013).

However, there are many stipulations when it comes to measuring the isotopic composition and methane/ethane ratios and then making inferences from that data. For instance, Stevens et al, 2017, investigated the impact of diffusive processes on methane isotopic composition as it travels from its source and diffuses through the Martian regolith and noted that this transport mechanism from the sub-surface could have a significant impact on the isotopic composition of the travelling gases. This effect was also depth dependent with the author stating that the deeper the source, the more chance and the greater the change in proportion of ¹³C from sources with a depth greater than 1km. This means that methane derived from an abiogenic source could present with a biogenic signature due to the alteration caused by this transport through the Martian regolith, assuming the source depth was sufficient (Stevens et al., 2017). The only thing that can be unambiguously inferred from methane isotope measurements is that a Delta ¹³C close to 0 or positive implies a shallow, abiogenic source (Stevens et al., 2017).

This is confirmed by Etiope, 2018, who states that the isotopic composition doesn’t necessarily indicate the origin of the Martian methane fully. For instance, micro-organisms can produce methane that is ¹²C depleted and can have an isotopic composition that resembles that of thermogenic gas. Drake et al, looked at stable isotopic analysis of calcite precipitated in bedrock fractures and found a staggering variability in the carbon isotopes in the calcites with values of δ13C spanning as much as -93.1‰ (related to anaerobic oxidation of methane) to +36.5‰ (related to Methanogenesis). This shows that microbial process can create very different isotopic signatures, even on Earth in terrestrial bedrocks (Drake et al., 2017). Figure 6 shows a summary of all the possible values associated with each potential origin pathway, there is considerable overlap and uncertainty concerning these values. Post-genetic alterations can also greatly modify the isotopic composition of methane gas (as seen in figure 6). They mention another pathway in which this change can occur by mentioning oxidation by hydrogen peroxide in the regolith which can increasing the proportion of ¹³C in the molecule, essentially turning the “biotic” signature into an “abiotic” signature, obscuring the molecule’s true origin. Furthermore, isotopic fractionation during diffusion in low permeability rocks can lead to ¹²C enrichment in the released gas, giving the gas a “microbial” signature (Etiope, 2018).

Additionally, methane/ethane ratios also do not give us a definitive answer and have many flaws as a method of determining a gas’ origins. For instance, high methane/ethane ratios (greater than 1,000) are often suggestive of a microbial gas; however thermogenic gas can also have a methane/ethane ratio that is similar to a microbial gas signature. In addition to this, an abiotic gas can have a wide methane/ethane ratio which can overlap with that of thermogenic gas and a microbial gas, further obscuring any ratio analysis (Etiope, 2018). Figure 7 shows the potential origin mechanisms associated with each methane/ethane ratio and, similar to figure 6, there is much uncertainty. Lab experiments have shown that the lower the temperature of the inorganic reaction, the lower the energy needed for polymerisation of methane molecules to form longer chain hydrocarbons. Furthermore, Martian microbes may have evolved to release different quantities of methane and ethane, thus further throwing off any attempt to use a ratio to determine a gas’ origin. And, similar to methane’s isotopic composition, transport through the Martian regolith may change the methane/ethane ratio due to molecular fractionation or segregation as it travels. Finally, once the ethane has reached the atmosphere, it may be more rapidly oxidised than methane, further complicating the ratio. Overall, there are many flaws when it comes to using the ratio between methane and ethane in the Martian atmosphere (Etiope, 2018). It’s been proposed that they can be mitigated by integrating NOMAD observations with geological analyses of potential gas emission sites whose locations can be estimated through atmospheric circulation modelling, it would also be beneficial if future missions analysed the gas directly from the soil/subsurface (Etiope, 2018).

Isotopologues:

Isotopologues are molecules that differ only in their isotopic composition, for instance CH₃D or CH₂D₂ (D referring to Deuterium, an isotope of hydrogen). They can provide information as to what the temperature was during CH₄ formation and therefore help provide insight into its production. This information is gathered through a process called isotopologue thermometry, which is generally only reliable at temperatures exceeding 150 degrees celsius, when isotopologues are in thermodynamic equilibrium. In order to understand whether ¹³CH₃D is in isotopologue equilibrium, a second isotopologue is also needed ¹²CH₂D₂. This cannot be measured by NOMAD. Additionally, the combination of these 2 isotopologues is also important for understanding any potential microbial inputs. This is because both biotic and abiotic methane gas can be generated at low temperatures and the ¹³CH₃D isotopologue thermometry data can be hard to interpret in this case. The ¹³CH₃D can be useful in helping to differentiate between high temperature biotic thermogenic methane and magma-derived gas. (Etipoe, 2018)

Future Martian Missions:

Rosalind-Franklin Rover:

This mission rover is designed to search for signs of life. It will do this by looking at morphological and chemical signs on the Martian surface/near-surface. It will not analyse the atmosphere directly, although the lander that is deploying the rover is equipped with a meteorological station. The study of morphological study may yield some important information as biological processes that may have occurred could be preserved on the surface of rocks or beneath the planet’s surface. The rover will also help to study the geology of the planet which is important as it will inform us in regards to the impact of post genetic alterations on the methane as it travels through the regolith. The rover has a crucial piece of equipment aboard named the Mars Organic Molecule Analyser (MOMA) which detects organic molecules through laser desorption and thermal volatilisation followed by GC-MS (NASA.gov). This GC-MS capability will be able to analyse the composition of rocks and inform us if there is methane present within them. Safir et al, 2019, suggests that methane can be released through Aeolian abrasion occurring due to particles carried by Martian winds colliding. GC-MS could help not only help confirm the presence of methane on Mars but may also provide guidance for potential sinks and release mechanisms, as proposed by Jensen et al, 2014 and Safir et al, 2019.

Perseverance Rover:

In addition to the Rosalind-Franklin rover, there is a new mission that is currently underway and touched down on Thursday 18th February 2021, the Perseverance rover. This mission is designed to look for evidence of a past Martian environment capable of supporting life, along with seeking out life in those environments. It does this through two main pieces of specialise equipment. The “SuperCam” which is capable of providing imaging, chemical composition analysis, and providing information on mineralogy in rocks and regolith from a distance. This will be able to provide valuable information pertaining to Martian geology which is important to gather information about potential alteration that may occur and the Scanning Habitable Environments with Raman and Luminescence for Organics and Chemicals (SHERLOC) provides fine imaging and a UV laser to determine fine scale mineralogy and to detect organic compounds. This could confirm the presence of organic matter close to the Martian surface. This is important as a proposed generation pathway of methane is the UV breakdown of organic matter, so showing that organic matter exists in close proximity to the surface could suggest that this mechanism is an important driver of methane production on Mars (NASA.gov).

Potential Future Missions:

There are gaps in the literature concerning methane on Mars and future missions will need to focus on some main areas to advance our understanding. Firstly, direct experimentation on the surface or just beneath will be invaluable. This will help us gather information about the Martian sub-surface geology which will inform us about potential alteration mechanisms occurring as methane is transported through the Martian regolith. The Rosalind-Franklin rover will help inform us of this as it will be taking sub-surface samples of Martian geology, as will Perseverance. Secondly, the retrieval of Martian samples to be directly examined back on Earth will also be invaluable. This is a long-term goal which Perseverance is a part of this. Perseverance will collect samples and stash them on the planet’s surface for a subsequent pick up mission. There are current proposals for a follow-on mission that will involve a NASA-led retrieval lander that will retrieve the samples and launch them into orbit where they will meet a ESA-led return orbiter that will return to Earth where they can be examined directly with advanced Mass Spectrometry to ascertain their exact composition (NASA.gov). Analysing these samples with-Mass-Spectrometry-will-be-vital-to-verify-the-presence-of methane on Mars, along with helping to verify the idea of Jensen et al, 2014, concerning the reaction of methane to eroded quartz grains as methane sinks.

Additionally, gathering a greater understanding of the dynamics of the Martian atmosphere could also allow for a deeper understanding concerning the spatial variations seen in methane observations along with any potential loss mechanisms. By correlating at this potential atmospheric data with geological data could be invaluable in uncovering potential sites of methane generation and potential methane sinks. Further, gathering accurate direct wind measurements would allow for back-trajectory simulations which would aid in pinpointing the origins of methane plumes. For instance, Lefèvre and Forget, 2009, conducted Martian general circulation models which simulated 10 potential source locations for a methane plume detected by the TLS but all the source locations were equally likely due to a lack of observational constraints (Lefèvre and Forget, 2009). To gather this data, a network of meteorological stations could be set up with a series of in-situ sensors that will gather data relating to temperature, pressure and humidity with wind masts that could be used to gather wind measurements (Yung et al., 2018).

Conclusion:

To conclude, there is still much uncertainty about the abundance of methane in the Martian atmosphere- early observations observed methane concentrations ranging from 3-15ppbv (figure 2) but these observations were not reinforced by TGO. The current literature has ruled out the input of volcanic activity due to the lack of detectable SO₂ (Encrenaz et al., 2000), the spatial variability of detected methane cannot be explained by exogenous sources including interplanetary dust, meteorites and comets (Atreya et al, 2007) and the UV photolysis is unlikely to be able to produce the required amounts of methane to cause concentrations observed (Taysum and Palmer, 2020), meaning another mechanism must be occurring. This leaves serpentisation of ultramafic rocks and biotic methane as the two leading hypothesises. The quick loss of methane implies that additional removal processes in addition to oxidation and photolysis must also be occurring (Bertaux et al., 2012). The leading hypothesises include the presence of a strong oxidiser like hydrogen peroxide, the reaction of methane with eroded quartz grains and methane adsorption to the Martian soil. Methane adsorption is unlikely to be the loss mechanism as it can only sequester methane for months which isn’t long enough to account for the loss methane, although could be used to account for seasonal variation (Gough et al., 2010). An oxidiser being responsible for the quick loss of methane is possible as hydrogen peroxide was confirmed to be present in the Martian atmosphere and in concentrations of ~40ppbv (Atreya et al., 2007). However, the most likely mechanism currently is the reaction of methane with eroded quartz grains as this has been confirmed to be possible in laboratory experiments (Jensen et al., 2014) and Safir et al, also suggests that the reverse process is also possible as methane can be released through Aeolian abrasion of quartz grains due to wind on the surface causing the collision of particles (Safir et al., 2019).

There is still uncertainty surrounding the origins of Martian methane as current analysis is too inconclusive to draw strong conclusions due to the potential impact of post genetic alterations acting upon any methane released (figures 6 and 7) (Etiope, 2018). Therefore, to yield the most accurate results future missions will need to incorporate an in-situ analysis of gas coupled with a better understanding of the geology of the Martian sub-surface.